|

By Julia Campbell, HRNK Research Intern

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research July 14, 2022 The people of North Korea are subjected to serious human rights violations on a daily basis. These include the exploitation of children for labor and the imposition of harsh punishments for “crimes” that are seen as dangerous to the regime, such as watching South Korean dramas, distributing foreign media content, or attempting to escape the country. However, there are sub-groups of people who are particularly vulnerable, one being the women of the North Korean military. In North Korea, women experience extreme oppression from men who are in positions of official authority. This can be even worse for women in the military. Women in North Korea are required to serve in the military, but this was not always the case. According to Daily NK, in 2015, North Korea made military service mandatory for women between the ages of 17 and 20. Women are required to serve until the age of 23.[1] Some of the horrific treatment and conditions women face in the military include sexual assault, brutal physical punishments, forced abortions, lack of feminine hygiene products, and the use of threats to shame and silence women. This essay describes these conditions in greater detail by recounting the testimonies of several women who served in North Korea’s military, formally known as the Korean People’s Army (KPA). In an interview with the BBC, Lee So-Yeon, a former KPA soldier, describes the conditions she faced. To begin with, patriarchal ideology was emphasized in the military. In addition to basic training, women had to do household chores such as cooking and cleaning. Men were exempt from such chores. With inadequate food and stressful training, Lee explains that women would stop having periods, and if they did have them, they would have to reuse sanitary pads and wash them when the men were not looking. She also recalls that women could rarely shower due to the lack of hot water. They had to use a hose to shower, and at times frogs and snakes would come out of the hose.[2] Lee and her fellow soldiers were not given the necessities for proper hygiene. Sexual assault and rape were also prevalent. Lee did not experience this herself, but she said many of her comrades had. She states, “The company commander would stay in his room at the unit after hours and rape the female soldiers under his command. This would happen over and over without an end.”[3] Rape in the military was commonplace, and the victims were often blackmailed into silence. According to Hyun-Joo Lim, a senior lecturer at Bournemouth University, “Being able to join the Worker’s Party of Korea is an essential pathway to a secure, successful life in North Korea, and a major reason for women to join the army is to become a member of the party. Senior male officials frequently exploit this as a means to manipulate and harass young women, threatening to block their chances of joining the party if they refuse or attempt to report the abuse.”[4] Unable to report their abusers, women face an endless cycle of suffering. Another alarming aspect of being a woman in the North Korean military is what women must do when they become pregnant. Women are blamed for the pregnancy, so they utilize dangerous methods to abort. This includes “tightening their stomach with an army belt to hide their growing pregnancy, taking anthelmintic medicine (antiparasitic drugs designed to remove parasitic worms from the body), or jumping off and rolling down the high mountain hills.” Lim adds a horrific detail, based on testimony from escapees: “it’s common to find foetuses in army toilets.”[5] That women are willing to put their own health and safety at risk in this way highlights their fear and shows just how difficult life is for women in the North Korean military. The testimony of North Korean escapee Jennifer Kim (alias), originally featured in a video interview by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK), provides another illustration of women’s experiences in the KPA.[6] Kim and other female soldiers faced cruel punishments. She recalls one punishment that involved dipping one’s hands into freezing water then placing them on iron bars. When the hands were removed, so was a layer of flesh. This would happen to all the women if even one person made a mistake. Kim was sexually assaulted when she served in the military. She was called to a political advisor’s office when she was 23 years old and had a gut feeling about what was going to happen, but she was unable to refuse his order. Kim states, “If I refuse his request, I can’t become a member of the of the Workers’ Party of Korea...If I return to society without being able to join the party, I’m perceived as a problem child and I will be stigmatised for the rest of my life.”[7] Kim ended up becoming pregnant and experienced a traumatic abortion. Kim describes her horrific experience as follows. “I went to the military medical office... a military surgeon was already waiting for me. He performed an abortion on me without anaesthesia...It still haunts me today.”[8] This has had a lasting impact on Kim’s life. She still struggles with mental issues, cannot have children, and has difficulty having a good marriage. All available evidence indicates that Kim’s experience is not an isolated incident. Da-Eun Lee, a North Korean escapee living in South Korea, talks about her horrific experiences in the military in a video interview cited by Business Insider.[9] When she was 18 years old, a 45-year-old major general asked to speak to her alone. He ordered her to disrobe, stating that he had to “[inspect] her for malnutrition, possibly to send her off to a hospital where undernourished soldiers are treated.” Lee recalls that “I didn’t have much of a choice,” assuming that “there’s a good reason for this.” The major general then ordered her to remove her underwear. When she refused and screamed, he brutally beat her until she was bleeding and had loose teeth. He also threatened her into silence by claiming he would make her life “a living hell.” The former soldier then explains how there was no one she could report her abuse to, and that many other women have also experienced this kind of abuse.[10] Female soldiers in North Korea’s military are subjected to serious human rights violations and abuse, including rape and forced abortions. According to witness accounts, sexual assault and the manipulation of women are commonplace. Women are unable to seek legal recourse. Because women are silenced, there is no justice. They have to live seeing their abuser go unpunished. Women may even experience continued abuse from their abusers due to the lack of accountability. This essay aims to highlight, once again, what happens to women in North Korea’s military and shed light on their testimonies to raise awareness of the horrific treatment they experience. Julia Campbell is a junior at Indiana University Bloomington's Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies, majoring in East Asian Languages and Cultures with a concentration in Korean. [1] Choi Song-Min, “Mandatory Military Service Extends to Women,” Daily NK, January 28, 2015. https://www.dailynk.com/english/mandatory-military-service-extends/. [2] Megha Mohan, “Rape and no periods in North Korea’s army,” BBC News, November 21, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-41778470. [3] Ibid. [4] Hyun-Joo Lim, “What life is like for North Korean women – according to defectors,” The Independent, September 7, 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/world/north-korean-women-rights-kim-jongun-domestic-violence-sexual-harassment-a8525086.html. [5] Ibid. [6] HRNK, “The Shocking Life of a North Korean Female Soldier: The Reality of North Korea!,” November 29, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MCsbikKfWLc. [7] Lorraine King, “North Korean soldier reveals horrific torment women face in Kim Jong-un’s army,” The Mirror, December 21, 2021. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/north-korean-soldier-reveals-horrific-25751688. [8] Ibid. [9] The video interview, with English subtitles, can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbcxTJKJOVI. [10]Alex Lockie, “Female North Korean soldiers describe horrific sexual abuse from superior officers,” Business Insider, August 28, 2017. https://www.businessinsider.com/female-north-korean-soldier-horrific-sexual-abuse-2017-8.

0 Comments

Denying the Refugee: a Comparative Analysis of China and the EU’s Use of the Term “Economic Migrant”6/14/2022 By Bryan Clark, HRNK Research Intern

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research June 14, 2022 From the United States denying entry to Salvadorans and Guatemalans fleeing their countries throughout the 1980s, to Australia refusing Vietnamese “boat people” in the early 1980s, classifying refugees as “economic migrants” is not a new phenomenon.[1] However, it is one that has become increasingly common in the 21st century. Many argue that by claiming asylum, economic migrants seek to bypass immigration laws in search of a more stable and prosperous economic environment. However, the term “economic migrant” has been used in many instances to deny protection to refugees fleeing horrendous circumstances. Moreover, it has been used to justify returning refugees to countries where their safety is threatened. Two poignant examples of this are China and the European Union’s (EU) forcible return of refugees under the guise of them being “economic migrants.” The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (hereafter referenced as the 1951 Refugee Convention) and its 1967 Protocol are the two most fundamental treaties in international human rights law for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees. These treaties set out the definition for what a refugee is, their rights, and states’ obligations to them. One of the key elements of the 1951 Refugee Convention is the principle of non-refoulement, which states that refugees cannot be returned to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened based on race, religion, nationality, social group, or political opinion.[2] Under these instruments, signatory states are required to conduct Refugee Status Determination (RSD) procedures to ascertain if an asylum applicant is capable of receiving refugee status under international, regional, or national laws.[3] What adds further complexity is the vague and limited scope of the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. As stated by Goedde, a strict reading of the 1951 Refugee Convention hindering the acceptance of North Koreans who flee their country as refugees is consistent with what is happening to refugees in other parts of the world, who are not well received by other states.[4] While the principle of non-refoulement is explicitly stipulated, the definition of “refugee” in both documents is too narrow. This allows states to disregard the danger that many asylum seekers find themselves in should they return to their own country. Unfortunately, states do not have many incentives to expand this definition, as the perceived burden of distinguishing between refugees and economic migrants has led many states to increase their standards of proof in determining refugee status.[5] In China For decades, North Korean refugees have fled into China to escape the grim reality of life under the Kim dynasty. The specific reasons for leaving are varied, but some of the most common are food insecurity, political persecution, and lack of religious freedom. Varied estimates place the number of North Korean refugees living in China between 60,000–100,000, the majority of whom reside in the northeastern Chinese provinces along the border with North Korea.[6] Yet, despite having finally escaped the brutal regime, North Korean refugees in China live under the constant threat of being sent back if discovered. The Chinese government denies North Korean refugees the right to asylum by classifying them as economic migrants. It claims that many North Korean refugees enter China to make money to feed themselves or their families. This has been the long-standing position of the Chinese government. Beijing has several agreements with the North Korean government regarding border issues, including one on the repatriation of those who cross irregularly into China. The most notable of these agreements are the “Mutual Cooperation Protocol for the Work of Maintaining National Security and Social Order and the Border Areas” signed in 1986 and a secret repatriation agreement signed in the 1960s.[7] These agreements require China to return any North Korean “migrants” who have illegally crossed into the country. From the Chinese government’s perspective, it considers itself obligated to comply with these agreements, despite having ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.[8] Moreover, in 2002, China’s ambassador to South Korea stated that North Koreans illegally crossing into China could not be seen as refugees. Thus, China would protect its borders and treat those who have crossed “according to humanitarian political principles.”[9] However, the act of returning individuals China claims to be “economic migrants” to North Korea is a violation of the principle of non-refoulement, as enshrined in Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention. It has been well-documented by testimonies from North Korean refugees that those forcibly returned to North Korea are placed in prison camps. In these prisons, torture, rape, forced abortions, and death due to mistreatment regularly occur.[10] The Chinese government’s response ignores the roots of the dire predicament that many North Koreans face. The discriminatory nature of North Korean society, based on songbun, means that certain segments of the population are faced with severe economic discrimination, significantly limiting an individual’s access to sustenance based on social standing, religion, and political opinion.[11] Furthermore, no matter their original intention for leaving, those who flee North Korea become refugees the moment they cross the border. The majority of those leaving North Korea are not political dissidents as such.[12] However, due to the repressive and vindictive nature of the North Korean regime, these refugees are considered as traitors the moment they cross the border into China. Thus, even a North Korean leaving the country for economic reasons becomes a refugee sur place in China due to the credible fear of persecution upon return.[13] In the EU The refoulement of refugees in the 21st century under the justification that they are economic migrants has not been solely limited to North Korea’s most significant ally, but one of North Korea’s harshest critics as well. Like China, the EU has been involved in returning refugees to countries where their safety is threatened. The EU also widely claims to treat refugees in accordance with human rights law and principles. Yet, despite the prevalence of its humanitarian discourse, the EU has also denied asylum to refugees seeking protection from unsafe conditions in their home countries. Through the use of the label “economic migrant,” the EU has shirked its responsibility to protect vulnerable individuals. The EU is party to a robust and comprehensive regime of human rights laws that is intended to protect the fundamental rights of all individuals in Europe. Like China, the EU’s member states are bound to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol.[14] The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) obliges its signatories to respect human rights, including prohibitions against torture and the collective expulsion of aliens. Additionally, Article 78 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union explicitly requires the EU to ensure compliance with the principle of non-refoulement.[15] Yet, despite its humanitarian discourse and legal commitments to international and regional human rights laws, the EU has allowed the Mediterranean Sea to become a hotbed for human rights violations by its member states and one of its own agencies. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, also known as Frontex, is the EU agency tasked with securing the external borders of the Schengen Area. Frontex states that, in line with the EU’s expressed values, the agency operates in a manner that respects fundamental rights.[16] Despite these claims, Frontex has been embroiled in controversy in recent years due to repeated claims of being complicit in human rights violations against refugees. A 2021 report by Der Spiegel and its partners claimed that Frontex works in conjunction with the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy to return refugees to Libya.[17] This has continued to occur despite the 2019 recommendations from the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe to cease returning refugees to Libya due to consistent reports of human rights violations.[18] Many of these refugees are placed in detention camps for undefined periods of time, where they are subjected to torture, rape, and slavery.[19] Reports on the conditions in these camps date to the early 2000s, particularly those by Human Rights Watch, which highlight the EU’s failure to abide by its own humanitarian discourse.[20] Identifying economic migrants posing as refugees has been prevalent in EU border security management and migration control as well. The nature of Frontex’s activities at the EU’s borders center on the “truthfulness” of those that are intercepted, rather than assessments of vulnerability.[21] This sentiment was reflected in 2019 when Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini announced a planned security decree that would target “economic refugees.” Salvini justified the decree by stating that Italy has already accepted too many “fake” refugees.[22] Italy plays an important role in this task, as its geographical location is at the EU’s external border along the Mediterranean Sea. The EU has used Italy to strengthen its border security management regime. The country’s EU-backed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Libya provides the Libyan government with financial and material support in exchange for curbing the flow of illegal migrants.[23] However, the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy’s dragnet tactics mean that even refugees are summarily returned without receiving a proper assessment of their vulnerability. Concluding Remarks The term “economic migrant” cannot be justifiably applied to North Korean refugees, nor is the label accurate for many who try to “irregularly” enter the EU. These refugees are fleeing their country to find safety. The consequences of this trend have been exacerbated by the rise in anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiments in developed countries in the 21st century. The perception of refugees in the EU was, in certain member states, negatively altered due to a substantial number of arrivals during the 2015 European migrant crisis.[24] The EU has repeatedly condemned the North Korean government for its human rights record. Most notably, the EU sponsored the 2003 resolution on North Korean human rights at the UN Commission on Human Rights.[25] It was in this resolution that the Commission expressed its concerns about the scope and gravity of human rights violations in North Korea, and the EU has since continued to sponsor resolutions on North Korean human rights at the UN. The EU has also levied sanctions against North Korea to pressure the government to cease its nuclear weapons program and to stop committing human rights violations. The most recent round of sanctions by the EU came in April 2022, specifically targeting eight individuals and four entities involved in financing the country’s nuclear programs. However, despite its criticism of North Korean human rights violations, the EU continues to return refugees to countries where they are subjected to the similarly horrendous treatment of North Korean refugees. The EU, as a purported bastion of respect for human rights, must cease the refoulement of refugees to Libya. Its continued collaboration with the Libyan government flies in the face of the principles and values it claims to be founded on. Furthermore, the 1951 Refugee Convention was created in light of the experiences of European refugees fleeing persecution during World War II.[26] Condemning the North Korean government while being culpable of exposing refugees to egregious human rights violations ultimately undermines the EU’s credibility as a normative power in the area of human rights. Additionally, the moral thrust behind the EU’s recent sanctions on China for human rights violations in the country’s Xinjiang region is jeopardized as well. It should be noted that certain EU member states willingly accepted thousands of refugees during the height of the European migrant crisis, such as Germany.[27] Much effort by the EU is also being directed to resettle Ukrainian refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion.[28] As important as these efforts have been, the EU and its member states are strongly encouraged to abide by their own commitments to human rights, as required by both international and regional human rights laws, in all instances.[29] Likewise, the Chinese government must not ignore the international human rights laws that it has signed, no matter the agreements that it has with North Korea. These laws take precedence over national laws and agreements between states. The forced repatriation of North Korean refugees back into the hands of a brutal regime violates what is considered to be a fundamental human right, the ability to leave one’s country, which is enshrined in Article 12(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[30] As these individuals would be subjected to serious and systematic human rights violations in North Korea, the Chinese government is obligated under international law to cease all forced repatriation of North Korean refugees. Additionally, as required by all states that are party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, China must conduct RSD to thoroughly assess an individual’s asylum claim without summarily apprehending and returning them to their country of origin. While the 1951 Refugee Convention may suffer from a lack of effectiveness and has a restrictive definition of what a refugee can be, it is still important for states to remember the spirit in which it was created. The Convention was designed to provide protection for some of the world’s most vulnerable individuals and groups, an endeavor that should continue to be pursued today. Bryan Clark is a second-year graduate student at the European School of Political and Social Sciences (ESPOL) at Lille Catholic University in Lille, France, pursuing a Master's in International and Security Politics. [1] William Deane Stanley, “Economic Migrants or Refugees from Violence? A Time-Series Analysis of Salvadoran Migration to the United States.” Latin American Research Review 22, no. 1 (1987): 132–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2503545; Stephen B. Young, “Who Is a Refugee? A Theory of Persecution,” In Defense of the Alien 5 (1982): 38–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23141002. [2] UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 189, p. 137, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html [accessed June 12, 2022]. [3] UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “Refugee Status Determination,” accessed June 12, 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-status-determination.html. [4] Patricia Goedde, “Determining Refugee Status for North Korean Escapees under International and Domestic Laws,” Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies 11 (2011): 143–60. [5] Ryan Bubb, Michael Kremer, and David I. Levine, “The Economics of International Refugee Law,” The Journal of Legal Studies 40, no. 2 (2011): 367–404. https://doi.org/10.1086/661185. [6] Andrei Lankov, “North Korean Refugees in Northeast China,” Asian Survey 44, no. 6 (2004): 856–73. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2004.44.6.856; Lee Jeong-Eun, “UN Asks China Not to Send 7 North Korean Refugees Back Home,” Radio Free Asia, March 15, 2022. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/refugees-03152022182731.html. [7] Lee Woo-young and Yuri Kim, “North Korean Migrants: A Human Security Perspective,” Asian Perspective 35, no. 1 (2011): 59–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42705323. [8] Roberta Cohen, “China's Repatriation of North Korean Refugees,” Brookings Institution, March 5, 2012. https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/chinas-repatriation-of-north-korean-refugees/. [9] Lankov, “North Korean Refugees in Northeast China.” [10] “China: Redoubling Crackdowns on Fleeing North Koreans,” Human Rights Watch, September 3, 2017. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/03/china-redoubling-crackdowns-fleeing-north-koreans; United Nations, Human Rights Council. Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 2014. [11] Russell Aldrich, “An Examination of China’s Treatment of North Korean Asylum Seekers,” North Korean Review 7, no. 1 (2011): 36–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43908831. [12] Lankov, “North Korean Refugees in Northeast China.” [13] Aldrich, “An Examination of China's Treatment of North Korean Asylum Seekers.” [14] Rosie Rooney and Marta Welander, “On Its 70th Anniversary, the Refugee Convention Faces Unprecedented Threats across Europe,” Oxford Law Faculty, July 22, 2021. https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/07/its-70th. [15] European Union, Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, October 26, 2012, OJ L. 326/47-326/390, https://www.refworld.org/docid/52303e8d4.html [accessed May 24, 2022]. [16] Frontex, “Fundamental Rights,” accessed May 24, 2022. https://frontex.europa.eu/accountability/fundamental-rights/fundamental-rights-at-frontex/. [17] Sara Creta et al., “How Frontex Helps Haul Migrants Back to Libyan Torture Camps,” Der Spiegel, April 29, 2021. https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/libya-how-frontex-helps-haul-migrants-back-to-libyan-torture-camps-a-d62c3960-ece2-499b-8a3f-1ede2eaefb83. [18] See “Third party intervention by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights under Article 36, paragraph 3, of the European Convention on Human Rights Application No. 21660/18 S.S. and others v. Italy,” https://rm.coe.int/third-party-intervention-before-the-european-court-of-human-rights-app/168098dd4d. [19] Human Rights Watch, “Pushed Back, Pushed Around,” September 21, 2009. https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/09/21/pushed-back-pushed-around/italys-forced-return-boat-migrants-and-asylum-seekers. [20] Human Rights Watch, “Closed-Door Immigration Policy Is Shameful Vision,” September 15, 2004. https://www.hrw.org/news/2004/09/15/closed-door-immigration-policy-shameful-vision. [21] Katja Franko Aas and Helene O. I. Gundhus, “Policing Humanitarian Borderlands: Frontex, Human Rights and the Precariousness of Life,” The British Journal of Criminology 55, no. 1 (2015): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu086. [22] “Italian Mayors Clash on Salvini’s Migrant Decree,” InfoMigrants, January 4, 2019. https://www.infomigrants.net/fr/post/14307/italian-mayors-clash-on-salvinis-migrant-decree. [23] Yasha Maccanico, “Analysis: Italy renews Memorandum with Libya, as evidence of a secret Malta-Libya deal surfaces,” Statewatch, March 2020. https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/analyses/no-357-renewal-italy-libya-memorandum.pdf. [24] Dominik Hangartner et al., “Does Exposure to the Refugee Crisis Make Natives More Hostile?,” American Political Science Review 113, no. 2 (2019): 442–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000813. [25] David Hawk, Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea: the Role of the United Nations (Washington D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2021). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Hawk_UN_FINALFINAL_WEB.pdf. [26] “What Is the 1951 Refugee Convention-and How Does It Support Human Rights?,” Asylum Access, July 24, 2021. https://asylumaccess.org/what-is-the-1951-refugee-convention-and-how-does-it-support-human-rights/. [27] “Germany on Course to Accept One Million Refugees in 2015,” The Guardian, December 8, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/08/germany-on-course-to-accept-one-million-refugees-in-2015. [28] “Ukraine: EU Agrees Plan to Aid Refugee Resettlement,” Deutsche Welle, March 28, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-eu-agrees-plan-to-aid-refugee-resettlement/a-61277944. [29] UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “UNHCR’s Key Calls to the European Union to Better Protect Refugees,” February 1, 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/europeanunion/. [30] UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, December 16, 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3aa0.html [accessed June 10, 2022]. By Damian Reddy, HRNK Legal Counsel and Project Development Associate

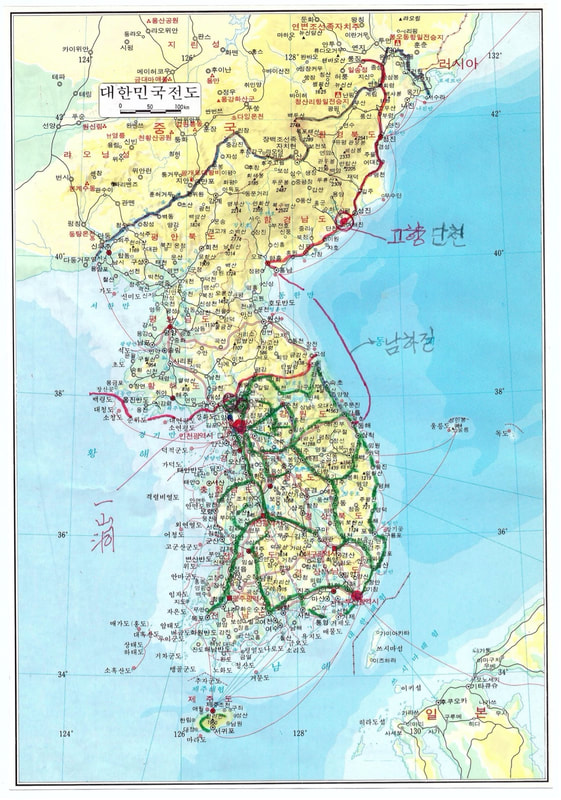

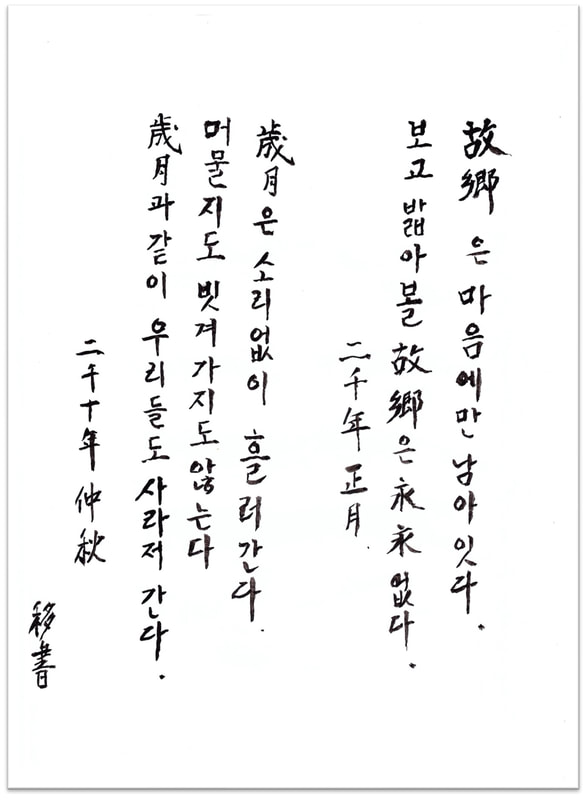

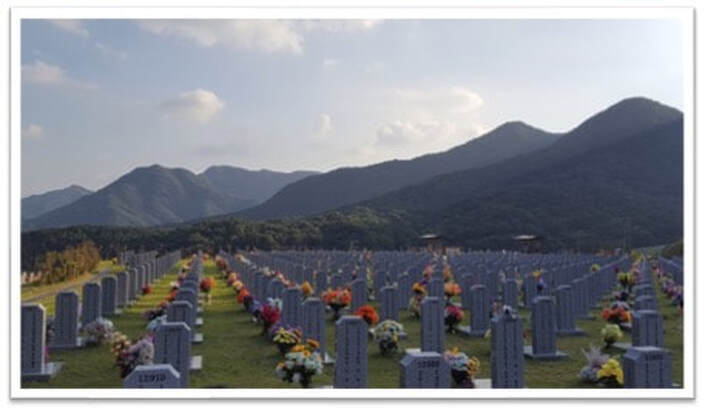

Edited by Eric Ryu, former HRNK Research Intern & Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research May 23, 2022 The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), also known as the “hermit kingdom” because of its extreme isolation from the rest of the world, is notorious for its human rights violations. According to the 2014 report of the UN Commission of Inquiry (hereafter “Report”), its human rights record is “without parallel in the contemporary world.”[1] Under the Kim family’s rule, the North Korean regime has terrorized its people for over seventy years. Those who attempt to cross the border are seriously punished if caught. Those who successfully escape are at risk of suffering from another evil: forcible repatriation. While this issue of forcible repatriation has previously been addressed, very little has been done on the ground. This essay seeks to not only serve as a reminder of this vital issue, but also urge relevant countries to act. Simply condoning forcible repatriation is a major violation of international human rights law. International Human Rights Violations by the North Korean Government under the Kim Family The DPRK has ratified significant international human rights treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC); and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).[2] Despite being bound by these treaties, the North Korean regime is notorious for ignoring the rules. To date, there has regrettably been little progress in improving the human rights situation in the DPRK. After extensive investigation, the 2014 Report of the UN Commission of Inquiry concluded that “the North Korean government systematically violated human rights including freedom of thought, expression and religion; freedom from discrimination; freedom of movement and residence; and the right to food.”[3] It further concluded that the DPRK had committed all crimes against humanity as listed in Article 7(1) of the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court, except for the crime of apartheid. The government vehemently denies having any part in the ill-treatment of its people and refuses to comply with international human rights standards. The Report is well-documented, however, and provides sufficient evidence detailing the North Korean government’s continued violations of international human rights law. The North Korean regime’s human rights record has been a regular topic of discussion at the United Nations (UN). Since 2005 and 2003 respectively, the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council have passed annual resolutions condemning the DPRK for its human rights record. There has been an emphasis on pursuing accountability, especially after the 2014 Report of the Commission of Inquiry. Furthermore, in 2019, the North Korean regime underwent its latest Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council,[4] where it only accepted 132 out of 262 recommendations.[5] This is a clear indication of the government’s indifference to international law and human rights mechanisms, which has been the North Korean regime’s attitude towards human rights since 2009, when the DPRK underwent its first review and did not accept any recommendations. While the most recent review shows some willingness to respond, it is important to remember that accepting recommendations does not necessarily mean that the regime implements them. Since 2019, the North Korean regime has increased measures to prevent its citizens from leaving the country. North Korean law criminalizes the act of leaving the country without official permission.[6] People who are caught trying to leave are apprehended and subjected to punishment, including, inter alia, public forms of punishment, imprisonment, and sometimes death.[7] The government has also encouraged the Chinese government to thwart the ability of North Koreans trying to escape by repatriating them to the DPRK.[8] Such repatriation is followed by harsh consequences. This is an egregious violation of the principle of non-refoulement, a sacred tenet of international law. It is the harsh treatment by the North Korean regime that forces citizens to leave, even when the risks are high and life-threatening. Food shortages, a failing economy, and severe consequences for not obeying the regime are among the many reasons driving people to escape. It is unfortunate that tighter border control and the emergence of Covid-19 have resulted in a drop in the number of escapees in recent years.[9] However, based on publicly available information, there seems to be a trend of higher-ranking officials who are attempting to escape.[10] The continued attempts to escape are a clear indication of the North Korean regime failing to meet its responsibilities and duties to the people under international human rights law. People would not risk their lives to escape if they were truly happy. International Human Rights Violations by China Most North Koreans attempting to escape the tyrannical rule of the Kim regime first attempt to enter China en route to South Korea, the United States, or other destinations. However, the Chinese government has been cracking down on North Korean escapees, capturing and forcibly repatriating them to the DPRK, where they are subjected to harsh consequences. The Chinese government argues that North Koreans are not seeking asylum or refuge but are simply looking for economic opportunities. The government terms them as economic migrants.[11] However, the lack of formal assessments for the escapees and such arbitrary repatriation are violations of international human rights law. China is notably a member of the Refugee Convention and the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, having acceded to the convention and Protocol in 1982.[12] A cornerstone of the Refugee Convention is the principle of non-refoulement in Article 33, which states that “no Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”[13] This means that a refugee should not be returned to a country if he or she faces serious threats to life or freedom. The term refugee is given a wide interpretation and includes asylum seekers.[14] The UN Human Rights Council refers to asylum seekers as prima facie refugees and affords them the same treatment as that of formally recognized refugees.[15] China is failing to uphold its obligations under the Refugee Convention by arbitrarily labelling North Korean escapees as economic migrants and simply sending them back while knowing the consequences these individuals could face. The Refugee Convention calls for a proper assessment to be conducted before an individual is repatriated, which the government is failing to do.[16] The submission to the principle of non-refoulement is especially important for North Koreans because repatriation results in severe punishment and even death.[17] China’s current practice of violating the principle of non-refoulement directly undermines the principles of the international refugee protection regime enshrined in the Refugee Convention. In addition, China ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) in 1988.[18] The CAT is clear when it references the principle of non-refoulement by stating in Article 3 that “No State Party shall expel, return ("refouler") or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”[19] It goes further to implore governments to consider all relevant circumstances and propensities of human rights abuses before deciding whether or not an individual is to be repatriated.[20] The scope of CAT is wider than the Refugee Convention, as it applies the principle of non-refoulement to all human beings, making no distinction between refugee and asylum seeker.[21] Furthermore, CAT refers to torture and ill-treatment as reasons for providing protection. These terms, especially ill-treatment, carry a wide and all-encompassing interpretation. In effect, this lowers the legal threshold for the Chinese government to comply with its responsibilities and duties under CAT when protecting North Korean escapees, who are escaping severe and harsh treatment by the regime. The term ill-treatment can refer to any justified form of serious fear to life or freedom as envisioned by the Refugee Convention and the CAT. China is a member to several other international treaties, all of which advocate for non-discrimination and the protection of all persons. CAT aptly mentions that all people are “members of the human family.”[22] Therefore, such arbitrary repatriation by the government is a clear violation of international human rights law, for which China has been reprimanded on numerous occasions. The Chinese government argues that it enjoys bilateral agreements with the DPRK that allows it to return North Korean escapees. However, when governments subscribe to treaty law, they are under a duty to put into place domestic measures and legislation compatible with their treaty obligations and duties.[23] This means that bilateral agreements contrary to international law and standards are, in principle, invalid. Therefore, the government cannot simply rely on its relationship with the DPRK. It is important to note that the 2014 Report of the UN Commission of Inquiry assigned liability on the Chinese government for aiding in crimes against humanity by its forcible repatriation of North Korean escapees. The Report highlighted evidence of Chinese officials being fully aware of the treatment of escapees, especially pregnant women who were—and still are—subjected to forced abortions by the North Korean regime.[24] The Report condemned the government for such inhumane violations of international human rights law. The Chinese government’s tendency to flout international law is not only a violation on its part, but consequently aids and abets the North Korean government in continuing to violate the human rights of North Koreans. China’s own human rights record has been far from commendable, especially since it has been preventing UN human rights officials from entering the country.[25] The Chinese government could bring immense, positive improvement to the plight of North Korean escapees by providing protection instead of returning them to a tyrannical regime. China should not rely on relationships or bilateral agreements to evade its international law responsibilities and duties. As rightly said by former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, loyalty should not be a reason to violate human rights.[26] International Human Rights Violations by South Korea (2019) In 2019, the South Korean government shockingly repatriated two North Korean fishermen who were discovered by the South Korean navy. According to official statements from Seoul, these two men were suspected of murder. The South Korean government’s decision to arbitrarily repatriate the two men was a violation of its domestic laws and international human rights law. Moreover, it called into question the integrity of the South Korean government and its commitment to upholding human rights. The government argued that the two men were serious criminals and were not eligible for protection. This, however, violates South Korea’s Constitution, which extends its domestic laws to all Koreans on the Peninsula.[27] By this standard, the two men should have undergone due process for their alleged crimes. Furthermore, South Korea’s refugee laws explicitly prohibit the refoulement of persons who seek refuge, even if he or she is not immediately identified as a refugee.[28] The principle of non-refoulement was clearly violated under the Refugee Convention and CAT. South Korea is a member state to both instruments. While the provisions of these treaties do not extend to non-political, serious criminals, such allegations must first be proved, and the treaties still do not condone repatriation in such circumstances when there is a serious fear to life and freedom. The South Korean government was criticized for its improper conduct. Besides the shame of violating domestic and international law, it was condemned for allowing diplomacy and bilateral relations to guide its decision-making at the expense of human rights. Many experts cautioned the Moon administration against allowing the pursuit of inter-Korean diplomacy to hinder honoring its human rights obligations. Again, fostering loyalty cannot be reason enough to flout the imperative to preserve human rights. Recommendations & Conclusion Human Rights Watch (HRW) suggested in 2002 that the North Korean government immediately stop its practice of punishing those who wish to leave the country, but to no avail. HRW has appealed to the government to repeal all laws, decrees, rules, and policies that result in any form of reproof. International verification has also been suggested to confirm that the government has indeed implemented these reforms. Furthermore, all detained persons are requested to be released with immediate effect, including non-residents who have been detained for assisting North Koreans to escape.[29] These recommendations remain valid, even more so as the situation seems to be worsening. HRW continues to make such recommendations, together with other international human rights organizations, including the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK), which continues to submit practical and specific measures for advancing human rights in North Korea. Some of these measures and recommendations include the following. The Chinese government is strongly urged to comply with its duties and responsibilities under international law. The government is requested to immediately stop the detainment and forcible, arbitrary repatriation of North Korean escapees until a proper and full assessment of the escapee has been conducted.[30] The government is also advised to allow access to and work with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to design and implement a workable process of assessing those persons escaping into China and to grant interim protection to North Korean escapees while due processes are conducted.[31] The Chinese government must bear in mind that it is an executive member of the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme which advises the UNHCR, so they are expected to maintain the standard in terms of its treatment of asylum-seekers and refugees according to international human rights law.[32] Governments around the world are encouraged to become more involved in issues that pertain to the repatriation of North Korean escapees, especially those who attempt to escape to China. Governments who enjoy bilateral agreements with the DPRK and China are urged to monitor and ensure that human rights standards are realized and upheld. In addition, this issue can be addressed at governmental meetings, forums, and conferences to ensure awareness and to discuss possible solutions. All suggestions should be relayed to the UNHCR for potential implementation. It is important that constant pressure is applied on China, and a constant spotlight is shed on China’s human rights record. Any positive appeals and proposals made by the UNHCR must be supported by governments around the world to increase pressure on the Chinese government.[33] The United States can, together with other countries—including South Korea, Japan, and EU member states—engage with China to discuss resettlement strategies, especially since most North Korean escapees resettle in South Korea or the United States. It is important to adopt a multilateral approach in the attempt to protect human rights.[34] While this may require complex bargaining and compromise, the result can be better if other governments can show a willingness to admit North Korean escapees instead. The South Korean government is called upon to adopt a more robust approach to human rights issues in the DPRK and to be more active in admitting and assisting North Koreans with resettlement. South Korea, as a country that accords constitutional rights to all Koreans in the entire Peninsula, should adopt legislation and policies to alleviate the human rights abuses faced by North Korean escapees. This is a recommendation of the 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry Report, which is yet to be fully realized by the South Korean government. There is much hope in the new Yoon Suk-yeol administration to advocate for human rights in the DPRK. Yoon has promised to make a greater effort to promote freedom and human rights around the world, including in the DPRK.[35] International human rights law was put into place to guide governments in protecting people against human rights abuses. Individual governments have the responsibility to honor their obligations under international human rights law. The issue of repatriating North Korean escapees has been an ongoing matter since the late 1990s, and it has still not been resolved. We should not forget that this is a serious human rights issue and strive to remember North Korean escapees in our efforts to defend human rights. Damian Reddy is a Law graduate of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and he is also an admitted attorney in South Africa. He is currently completing his Master of Laws degree in human rights. [1] UN Human Rights Council, “Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/hrc/coidprk/pages/reportofthecommissionofinquirydprk.aspx. [2] UN OHCHR, “UN Treaty Body Database: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” accessed May 23, 2022. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=47&Lang=EN. [3] UN Human Rights Council, “Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” [4] The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a unique process which involves a review of the human rights records of all UN Member States and provides the opportunity for each State to declare what actions they have taken to improve the human rights situations in their countries and to fulfill their human rights obligations. See https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/upr/pages/uprmain.aspx for further details. [5] “Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council on 23 March 2021: 46/17. Situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” Relief Web, accessed June 29, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-peoples-republic-korea/resolution-adopted-human-rights-council-23-march-2021-4617. [6] Article 63 of the Criminal Law of the DPRK (2015) refers to escaping the country as treason against the state. [7] Ibid. [8] U.S. Government Publishing Office, “China's Repatriation of North Korean Refugees: Hearing before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China,” March 5, 2012, accessed June 29, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-112hhrg74809/html/CHRG-112hhrg74809.htm. [9] See, for instance, the South Korean Ministry of Unification’s statistics on recent escapee arrivals at https://www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/business/NKDefectorsPolicy/status/lately/. [10] “North Korea’s Elite Defectors,” The Diplomat, accessed April 2, 2022. https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/north-koreas-elite-defectors/. [11] Joel R. Charny, “North Koreans in China: A Human Rights Analysis,” International Journal of Korean Unification Studies 13, no. 2 (2004): 75-97. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/47a6eba2o.pdf. [12] “China responsible and supportive on refugee issues: UNHCR representative,” Global Times, accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1201133.shtml. China is one of the first countries in Asia to accede to these instruments. [13] Article 33 of the Refugee Convention relates to the prohibition of expulsion or return (https://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10). [14] UNHCR, “Asylum-Seekers,” accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html. [15] Ibid. [16] Article 32(2) of the Refugee Convention indicates that a decision of expulsion must be made in accordance with the due process of law. The article allows for evidence to be adduced, representation to be made and appeals to be lodged against decisions. [17] Escaping North Korea is viewed as treason against the regime and is punishable by North Korean Criminal Law. [18] UN OHCHR, “UN Treaty Body Database: China,” accessed May 23, 2022. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=36&Lang=EN. [19] Article 3(1) of the CAT. [20] Article 3(2) of the CAT states that the competent authorities shall take into account all relevant considerations including the existence in the State concerned of a consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights. [21] See introduction of the CAT which states that the convention recognizes the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family. [22] Ibid. [23] United Nations, “The Foundation of International Human Rights Law,” accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/udhr/foundation-of-international-human-rights-law. [24] Congressional-Executive Commission on China, “UN Report Criticizes China for Treatment of North Korean Refugees Amid Worsening Situation,” accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/un-report-criticizes-china-for-treatment-of-north-korean-refugees. [25] Human Rights Watch, “UN: Governments Should Urge Xinjiang Inquiry,” accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/12/un-governments-should-urge-xinjiang-inquiry. [26] Judge Navi Pillay, “South Africa's Engagement with International Human Rights Law,” 15th Annual Human Rights Lecture to Celebrate the Centenary of the Law Faculty, University of Stellenbosch, May 20, 2021. [27] Article 3 of the Republic of Korea’s Constitution of 1948, with amendments through 1987. [28] Article 3 of South Korea’s Refugee Act (Act No. 14408) relates to the prohibition of compulsory repatriation, including those persons not yet recognized as refugees. See this link for an English translation of the law provided by the Korea Legislation Research Institute: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=43622&lang=ENG. [29] Human Rights Watch, “The Migrant's Story: Contours of Human Rights Abuse,” accessed July 5, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/northkorea/norkor1102.htm. [30] U.S. Government Publishing Office, “China's Repatriation of North Korean Refugees: Hearing before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China.” [31] This is referred to as prima facie refugees. [32] UNHCR, “UNHCR Representation in China,” accessed July 5, 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/hk/en/about-us/china. [33] U.S. Government Publishing Office, “China's Repatriation of North Korean Refugees: Hearing before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China.” [34] Ibid. [35] Choe Sang-Hun, “In Korea, a New President in the South Vows a Harder Line on the North,” The New York Times, May 11, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/10/world/asia/south-korea-yoon-president.html. By Teresa J. Y. Kim, HRNK International Outreach Fellow Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research Lee Min-Hak, a veteran of the Korean War (1950–53) and a North Korean refugee, never spoke of the war with his family during his lifetime. It was too painful to recount. He did, however, leave a journal behind. A few years after his passing, I watched my mother – his daughter – pull out his journal from under a pile of his belongings. She held back her tears as she began sifting through its pages. The journal is beautifully intact, its pages orderly and neat. In his journal entries, you can see faint pencil ruler markings underneath the dark, glossy black ink of his carefully written script of Hangul (the Korean language) and Hanja (the use of Chinese characters for writing in the Korean language). Following Lee Min-Hak’s service in the South Korean Army during the Korean War, he continued to serve in the army as a military engineer. He soon joined the officer corps (장교단) and eventually retired as a colonel (공병 연대장) from the Engineer Battalion. Lee received multiple awards for his service to the country from the government of the Republic of Korea. Most notably, he received awards from President Park Chung-Hee (October 1, 1971) and President Kim Young-Sam (June 1, 1993). He also received a medal from the United Nations acknowledging his role as a “6.25 War Correspondent” for the Republic of Korea, which is shown below.  The red markings on this map by Lee Min-Hak retraces his route from his hometown in Dancheon, northern Korea to the southernmost area of the Korean Peninsula in Busan. Lee met his wife close to the time of the armistice (1953) in Busan. On the left of the map, Lee circled his new home, Ilsan-dong, where his wife still lives to this day. © Teresa J. Y. Kim 2022. When the war first erupted, Lee Min-Hak was a young, 21-year-old schoolteacher in his hometown in Dancheon. One day, South Korean soldiers came to the playground of the school to warn him that he, being a schoolteacher, was in imminent danger. The soldiers offered him a seat on their truck that was leaving Dancheon that very day. Fearful of what the South Korean soldiers told him, Lee went home, packed a bag, and quickly said goodbye to his mother with the mind that he would return home once it was deemed to be safe again. He got onto the truck with the South Korean soldiers. Lee was then driven out of Dancheon. He neither returned nor saw his family ever again. Once he arrived in southern Korea, Lee chose to enlist as a South Korean soldier purely out of necessity. During the war, there was virtually no other choice for a young man like Lee. Not to mention, Lee was essentially a refugee, with no form of identity or a place to belong in unfamiliar surroundings. This was why Lee became a soldier. He had to survive and defend himself as a young Korean man living through war. The diary that Lee left behind offers deeply emotional entries about missing his hometown back in Dancheon, a port city in the north-eastern part of South Hamgyong Province in North Korea. Throughout his diary, he describes the agonising pain of not being able to reunite with his family members, who remained in Dancheon after the armistice was signed in 1953. Upon reading his writings, “missing” family seems like an understatement. What Lee conveys in his diary is a lifetime of deep sorrow, having been forcibly separated from his parents and siblings due to the war. Most of his entries express this unending sadness. Not knowing whether his family is still alive and if he will be able to reunite with them in a “unified Korea” is met with a heart-wrenching acknowledgement by those who are willing to resonate with a man’s experience of war. Lee Min-Hak was 86-years-old when he passed away on the 18th of May, 2016. He is now laid to rest among fellow veterans amidst the tranquil beauty of rolling hills and green landscapes provided as open spaces for loved ones to visit and pay tribute, especially during Chuseok (Korean Harvest Day), at the Daejeon National Cemetery (국립대전현충원). Lee’s life and legacy represents one of many narratives surrounding war, migration, and displacement. As aforementioned, Lee fought for peace so he could return back home to Dancheon to be with his family. Yet, his story is only one of countless experiences of people who were pushed into a life of war and displacement without being given a choice other than to fight. As a generation of Korean War veterans pass away, we must not forget why they fought in the first place. After all, to honour the efforts of advocating for North Korean rights is to honour the lives of people like Lee Min-Hak. This article is written by Teresa J. Y. Kim, granddaughter of Lee Min-Hak. Teresa J. Y. Kim is the International Outreach Fellow and Head of the Legal Research Division at HRNK. She received a Master of Laws (LLM) in International Law from the University of Edinburgh, with Distinction, in December 2021. Previous to this, she received a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in History and International Relations from King’s College London in 2020. Teresa hopes that in sharing Lee Min-Hak’s story, she can shed light on North Korean human rights in the context of a young Korean man who fought in the Korean War. All images used in this article are copyrighted by Teresa J. Y. Kim. By Audrey Gregg, HRNK Research Intern

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research March 8, 2022 On March 9, South Korea will hold its eighth democratic election since its transition to democracy in 1987. The next president will follow the incumbent, Moon Jae-in, a former human rights lawyer born to North Korean war refugees and whose presidency has been marked by his attempt, and failure, to improve diplomatic relations with North Korea.[1] The two forerunners are ex-civil rights attorney Lee Jae-myung and former public prosecutor Yoon Seok-yeol of the Democratic and People Power Party, respectively. Also in the running is Sim Sang-jung of the Justice Party, who is polling much lower.[2] Though this election cycle has largely focused on domestic issues such as housing prices, debt, and discrimination, the next president of South Korea will inherit the consequences of President Moon’s foreign policies and must pursue policies that balance the security of the citizens of South Korea, pressure from the international community, including the U.N., NGOs, and foreign governments, and the current human rights crisis in North Korea.[3] This election cycle has been dominated by mudslinging, scandals, and personal attacks. Over fifty percent of South Koreans do not care for either major candidate, and many feel that they are forced to choose between the lesser of two evils.[4] Yoon and Lee’s campaign platforms fall, for the most part, within the historical legacies of their respective parties. Policy surrounding North Korea has always been a divisive, partisan issue. Traditionally, the conservative People Power Party and its predecessors have taken a hardline stance, advocating for measures including the deployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons and stricter sanctions. In contrast, the Democratic Party favors diplomacy in the form of peace talks, summits, and inter-Korean dialogue.[5] Yoon has stated that foreign affairs, including diplomacy with North Korea, should be considered separate from human rights issues. In a press conference in January, he suggested that, "The only way to deter this threat is a pre-emptive strike using the Kill Chain,” a contingency plan that calls for identifying and destroying North Korean missile launch pads and facilities if an attack is deemed to be imminent.[6] Lee, on the other hand, prefers to roll back sanctions in hopes of denuclearizing North Korea, continuing peace talks and summits, and declaring an end to the Korean War.[7] His stance is reminiscent of the Sunshine Policy, a policy initiative pursued by former South Korean President Kim Dae-jung to provide economic assistance and encourage civilian exchanges between the two countries.[8] If it seems that one of these platforms is much more humane than the other, consider the fact the Sunshine Policy ultimately had little effect on inter-Korean relations.[9] Past experience demonstrates that promoting dialogue between the two Koreas usually comes at the cost of disregarding North Korea’s abysmal human rights record, as well as the voices of human rights activists who are silenced by the South Korean government to placate the North.[10] This is a common criticism of Moon Jae-in’s “Anti-Leaflet Law,” which was, according to Robert King, former Special Envoy for North Korea human rights issues at the U.S. Department of State, “in direct response to an acerbic public outburst against defectors from the North now living in the South by Kim Yo-jong.”[11] In 2019, South Korea declined to co-sponsor the UN Human Rights Council’s resolution on North Korea’s human rights situation, the same year it forcefully repatriated two North Korean fishermen without due process.[12] Despite these gestures and President Moon’s best efforts, Pyongyang responded with violence. It blew up the newly constructed liaison office at Kaesong, cut lines of communication with South Korea, and continued its missile tests. There is no evidence to suggest that a “gentler” approach to diplomacy in North Korea has been met in kind.[13] Clearly, a viable long-term solution must include policies that present Pyongyang with clear and meaningful incentives. Another controversy in the election campaign is the deployment of THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense), a U.S. defense system designed to detect and intercept ballistic missiles. Yoon fully supports the deployment of additional THAAD units and tactical nuclear weapons in an emergency, emphasizing the security of South Korean citizens and the importance of neutralizing North Korea’s nuclear capabilities over dialogue.[14] In his recent article in Foreign Affairs, he criticized the Moon administration, stating, “Dialogue with the North was once a specific means to a specific end: the complete denuclearization of North Korea. Under President Moon Jae-in, however, dialogue with the North has become an end in itself.”[15] Lee opposes the deployment of additional THAAD batteries, but is willing to accommodate the units that are already in the country.[16] THAAD also affects South Korea’s relationship with China, which retaliated to its initial deployment in 2017 with harsh economic measures.[17] So where does the upcoming election leave the people of North Korea, escapees who have resettled in South Korea, and the families of those who were abducted by North Korea? The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on North Korea’s economy, and many experts report that conditions within the country may be as dire as they were during the “Arduous March” of the 1990s.[18] Hundreds of thousands of North Koreans remain imprisoned without due process, and millions more endure systemic abuse, torture, surveillance, and other restrictions on their fundamental human rights. In the upcoming South Korean presidential election, diplomacy with North Korea is framed in terms of South Korea’s relationships with China and the U.S. Regrettably, there is no room at the bargaining table for the people of North Korea. Audrey Gregg is a graduate of New York University and has spent the last two years advocating for North Korean defectors residing in Seoul, South Korea. She has worked both in translation and resettlement efforts. [1] Charlie Campbell, “South Korean President Moon Jae-in Makes One Last Attempt to Heal His Homeland,” Time, June 23, 2021. https://time.com/6075235/moon-jae-in-south-korea-election/. [2] Editor’s Note: Ahn Cheol-soo, another third-party candidate, exited the race on March 3 and announced that he would join forces with Yoon. [3] “Campaigning for next President Kicks off in South Korea,” Al Jazeera, February 15, 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/15/campaigning-for-next-president-kicks-off-in-south-korea. [4] “Both Main Candidates for the South Korean Presidency Are Reviled,” The Economist, January 20, 2022. https://www.economist.com/asia/2022/01/20/both-main-candidates-for-the-south-korean-presidency-are-reviled. [5] “A Rundown of Leading Candidates' Positions on Defense, Foreign Relations and the Economy,” The Korea Herald, February 16, 2022. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220216000621. [6] Nam Hyun-woo, “Will North Korea Sway South Korea's Presidential Election?” The Korea Times, January 13, 2022. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2022/01/356_322153.html. [7] Choi Hyeon-ho, “Lee Jae-myung announces North Korea policy: conditional sanctions relief and step-by-step reciprocity” [in Korean], Gyeonggi Ilbo, August 22, 2021. http://www.kyeonggi.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2377465. [8] Norman D. Levin and Yong-Sup Han, “THE SUNSHINE POLICY: PRINCIPLES AND MAIN ACTIVITIES,” in Sunshine in Korea: The South Korean Debate over Policies Toward North Korea, 1st ed. (RAND Corporation, 2002), 24–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mr1555capp.9. [9] Ronald Popeski, “Sunshine Policy Failed to Change North Korea: Report,” Reuters, November 18, 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-korea-north-sunshine-idUSTRE6AH12520101118. [10] William Gallo, “Don't Ignore North Korea Human Rights, UN Says,” VOA, September 8, 2020. https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_dont-ignore-north-korea-human-rights-un-says/6195598.html; Jieun Baek, “A Policy of Public Diplomacy with North Korea,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School, August 2021. https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/policy-public-diplomacy-north-korea. [11] Robert King, “North Korea Human Rights and South Korea’s Upcoming Presidential Election,” Korea Economic Institute of America, January 19, 2022. https://keia.org/the-peninsula/north-korea-human-rights-and-south-koreas-upcoming-presidential-election/. [12] Ahn Sung-mi, “Seoul Declines to Back UN Resolution on NK Rights,” The Korea Herald, March 24, 2021. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210324000830; Eugene Whong, “South Korea Deports Two North Koreans Accused of Murder, Angering Rights Groups,” Radio Free Asia, October 11, 2020. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/nk-fishermen-deportation-11072019172700.html. [13] Victor Cha, “The Last Chance to Stop North Korea?” Foreign Affairs, February 2, 2022. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/north-korea/2021-09-22/last-chance-stop-north-korea. [14] “Yoon Pledges Additional THAAD Deployment after N.K. Launch,” Yonhap News, January 30, 2022. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20220130003100315; “Yoon Says He Will Request Redeployment of U.S. Tactical Nukes in Case of Emergency,” Yonhap News, September 22, 2021. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210922005300320. [15] Yoon Suk-yeol, “South Korea Needs to Step Up,” Foreign Affairs, February 8, 2022. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/south-korea/2022-02-08/south-korea-needs-step. [16] Ko Jun-tae, “Lee Jae-Myung against Beijing Olympics Boycott, Opposes THAAD Missiles,” The Korea Herald, December 30, 2021. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20211230000590. [17] Ibid. [18] Joung Eun-lee, “Is the North Korean Economy Under Kim Jong Un in Danger? ‘Arduous March’ in the Age of COVID-19?” 38 North, July 15, 2021. https://www.38north.org/2021/07/is-the-north-korean-economy-under-kim-jong-un-in-danger-arduous-march-in-the-age-of-covid-19/. |

DedicationHRNK staff members and interns wish to dedicate this program to our colleagues Katty Chi and Miran Song. Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed