|

Related Texts:

Taken! (2001) |

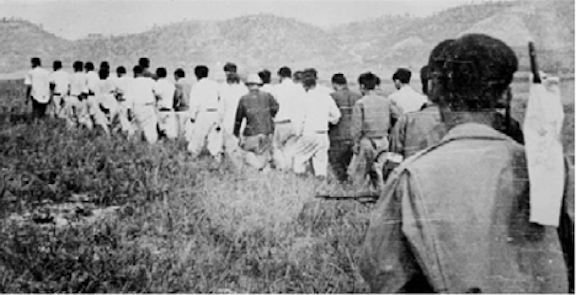

Abducted South KoreansInitially, people were abducted from South Korea during the Korean War. Soon afterwards, Koreans were lured from Japan and held against their will in North Korea. A decade later, children of North Korean agents were kidnapped apparently to blackmail their parents.

On July 31, 1946, Kim Il-sung issued an order to try to lure certain types of individuals—intellectuals and other educated professional people—to North Korea. He specifically stated, “In order to solve the shortage of intellectuals, we have to bring intellectuals from South Korea...” North Korea, devastated by the war, needed to replenish its population of farmers, miners, and factory workers. Just as Kim Il-sung’s pronouncements during the war drew intellectuals to the North who were then conscribed to hard labor, educated and often prosperous Koreans resident in Japan were also lured by the idea of helping to rebuild North Korea. They found themselves trapped in a nation that preferred to use their services in hard labor. By August 1950, United Nations and Republic of Korea forces had been pushed into a small area in the southeast corner of the Korean peninsula known as the Pusan Perimeter. North Korean forces controlled the rest of the peninsula, including Seoul. Seoul was liberated on October 28, 1950, and by that time, 82,959 citizens had been forcefully abducted and taken to the North. According to documents collected by the Korean War Abductees Family Union (KWAFU), these eighty thousand abductees included at least twenty thousand who were “politicians, academics, government ministers, and civil servants.” Their professional expertise, however, would not be put to use in the North. A Soviet document implacably recorded this loss of human capital, noting “the plan of transferring Seoul citizens to the North for their job placement in factories, coal mines and enterprises is being implemented in each related sector.” Starting in the years after the Korean War, many ethnic Koreans were encouraged to leave Japan and return to Korea. The majority were from South Korean families and almost one and one half million went to South Korea. Under a Chongryon-initiated project known as the Resident-Korean Returnees Project, those whose families had come from North Korea, or had sympathy for the regime, were urged to return to their motherland with the hope of building a prosperous socialist state. These returning immigrants were intended to supplement the North Korean labor force after it was decimated during the Korean War. During this period, Kim Il-sung’s North Korea was promoted as a “paradise.” As Kang Chol- hwan, a grandson of one of the returnees wrote, “The leaders of the Chosen Soren were very keen on seeing people with advanced education return to North Korea, and they continually played up the homeland’s need for individuals with knowledge and abilities. In North Korea a person could serve the people and the state rather than Japan, that pawn of American imperialism.” The project was also supported by many Japanese intellectuals, media, and the Foreign Ministry, largely out of guilt for the colonial exploitation of Koreans, in the belief that they would find better lives in their homeland. From the time the project started at the end of 1959 until the end of 1960, some 50,000 people boarded ships bound for North Korea. Rumors of harsh treatment in North Korea, however, began to leak out immediately. Censored letters from friends and family who had moved to North Korea held urgent requests for food and money. They also held carefully written but decipherable phrases that warned loved ones not to follow them. In 1961, the numbers suddenly decreased to less than half of the previous year; and only 22,801 returned. When the Project reached its fourth year in 1962, only 3,497 ethnic Koreans decided to participate. The returnees were greeted by North Koreans waving flags and shouting, “Welcome! May you live a long life!” Passengers were shocked by how unhealthy, thin, and poorly dressed the North Koreans were. Their faces were dry and dark with malnutrition. He concluded they were ordered to put on the welcoming demonstration, since no one from the crowd actually walked over to greet the passengers personally as they came off the boat. Chung realized he had become a victim of North Korean propaganda. Conditions for Korean abductees were different from those of non-Koreans. Since they spoke the same language and are considered to be of the “same race” by DPRK leadership, they were allowed to live among the general public after going through intense education and training. Ethnic Korean victims are often able to marry local women, move to different areas, become full-fledged DPRK citizens, and in some cases even become Workers Party members. Yet this difference in privileges did not always mean that ethnic Koreans lived a better life than the non-Korean abductees. They may actually have faced harsher conditions because they were treated like average North Korean citizens. And like other abductees, they were constantly watched by the State Security Department (SSD), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), and the Korean Workers Party (KWP). |