Who are the victims?

|

Being one of the most repressive states in the world, inciting fear is one of the ways the government maintains control over the population. The arbitrary arrests, foul prosecution, and torture of inmates render many individuals vulnerable, especially if they rank lower on the songbun system. The Korea Institute for National Agency estimates that there are between 80,000 and 120,000 people imprisoned in North Korea. In 2014, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry report on human rights in North Korea found that the government committed acts against humanity. They include: extermination, murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, and various forms of sexual violence.

|

Related Texts:

United Nations Commission of Inquiry |

Starvation food rations, forced labor, routine beatings, systematic torture and executions put the North Korean camps in the ranks of history’s worst prisons for political offenders.

Prisoners

|

Presumed political ideological, sociological deviations may warrant the deportation of individuals and their imprisonment in labor camps. They include people suspected of wrong-doing, wrong-thinking, wrong-knowledge, wrong-association, or wrong-class-background. These elements, which motivate the persecutive practices, mirror North Korean society.

A striking feature of the kwan-li-so system is the penal philosophy of “collective responsibility,” or “guilt by association” (yeon-jwa-je) whereby the mother, children and sometimes grand- children of the offending political prisoner are imprisoned in a “three-generations” practice. Former prisoners and guards align this practice with the 1972 statement by “Great Leader” Kim Il-sung: “Factionalists or enemies of class, whoever they are, their seed must be eliminated through three generations.” Another striking characteristic of the kwan-li-so system is that those citizens who are to be deprived of their liberty are not arrested, charged (that is, informed of their offense of, or against, a particular criminal act delineated in the DPRK Criminal Code), or tried in any sort of judicial procedure. There is no chance to appear before a judge, confront their accusers, offer a defense or have benefit of legal counsel. The presumed offender is simply picked up, taken to an inter- rogation facility and frequently tortured to “confess” before being deported to the political penal-labor colony. The family members are also picked up and deported to the kwan-li-so. None of the interviewees reported having been told of the whereabouts or alleged misconduct of the presumed wrong-doing or wrong-thinking head of family.

|

Former prisoner testimony

... |

Factionalists or enemies of class, whoever they are, their seed must be eliminated through three generations. |

Starvation |

Prisoners are provided only “starvation-level” food rations, even though they are forced to engage in long and physically demanding labor. This combination often turns the labor camps into death camps. |

--

The most salient feature of day-to-day prison labor camp life is the combination of below-subsistence food rations and extreme hard labor. In a system of intentional, administratively inflicted hunger, the regimen of chronic semi-starvation provides only enough food to be kept perpetually on the verge of starvation. Prisoners are driven by hunger to eat, if they can get it (and avoid being caught) anything remotely edible: plants, grass, bark, rats, snakes, the food-stuffs of the labor camp farm animals. According to the testimony of former prisoners, deliberate below-subsistence-level food rations in the camps preceded by decades the severe nationwide food shortages experienced by North Korea during the famine of the 1990s.

When entire families are deported to the camps, much of their household and personal belongings—clothing, blankets and bedding, pots, pans, cooking utensils, etc. are trucked along with them. However, these material possessions are soon bartered away for food. Former prisoners recall their shock upon initial arrival at the camps at the sight of the malnourished inmates: stick figures dressed in tattered, patched and threadbare clothing; and literally, rags. The prisoners are occasionally issued shoes, but not socks, so that rags are frequently wrapped around ankles for warmth. The prisoners are covered in dirt from the infrequency of bathing privileges, and marked by physical deformities: hunched backs, from years of bent-over agricultural work in the absense of sufficient protein and calcium in the diet; and missing toes and fingers, from frostbite; and missing hands, or arms or legs, from work accidents.

Eyewitness accounts establish that, in one case, out of 2,000 to 3,000 people in one section of one prison, 100 people died per year from malnutrition and disease, mainly from severe diarrhea leading to dehydration. A former prison guard reported that at Prison Camp No. 22, which housed approximately 50,000 prisoners, 1,500 to 2,000 prisoners died from malnutrition each year. That same guard stated that most of those who died were children. To ensure that prisoners stayed near starvation, attempts to obtain unauthorized food, even weeds, were punished by beatings and execution

The insufficient food rations cannot be attributed to a lack of food, because the below-subsistence rations predated North Korea’s famine of the 1990s. Instead, starving the prisoners helps control them. For example, prisoners are given strict and often unrealistic work quotas each day. Failure to meet one’s quota results in reduced food rations. This threat leads prisoners to work as hard as they can to avoid food reductions. As a result of insufficient food rations, death and disease caused by malnutrition is common in the camps.

Labor

|

All prisoners, including children, are required to engage in very demanding and dangerous labor at the various kwan-li-so. The work given to prisoners includes mining, timber-cutting, farming, and sewing. Prison labor conditions in some camps result in 20 to 25 percent of the labor force (i.e., political prisoners) being worked to death each year. A former guard reported that at kwan-li-so No. 22, there were so many deaths from beatings of prisoners who had not met their labor production quotas that guards were instructed to be less violent. If prisoners are able to avoid death, they still risk being disabled or losing a limb. Frostbite from working in freezing conditions with little protection from the elements causes amputations to be commonplace. Prisoners were not given clothes that could be called anything other than rags and were only given new shoes every two years. Because the shoes were not of good quality and the work was so demanding, the shoes never lasted more than one year.

|

Torture |

Torture: the “intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, upon . . . person[s] in the custody” |

#FreeThe20: North Korea |

Witness testimony has also revealed the systematic use of torture as a means of interrogation and punishment. When arrested, political prisoners are first tortured in an effort to get them to “confess.” Once placed in a camp, prisoners are further tortured as a means of punishment. A former North Korean intelligence agent, Kwon Hyok, confirmed that torture took place routinely: “[p]risoners were like pigs or dogs. You could kill them without caring whether they lived or died . . . .”

|

Executions and Extreme Punishments

North Korean citizens have been executed for a broad array of political crimes, including crimes that would not ordinarily be considered “political.” For example, individuals caught fleeing North Korea have been executed for engaging in “treason against the fatherland.” Members of an organized crime syndicate were executed because they shouted the name of their boss. This act was seen as showing respect for their boss, which was deemed to be a political crime. Being in possession of information regarding South Korea is also an act punishable by execution. One individual was executed for being in possession of a gun and a South Korean leaflet. Similarly, a sergeant in the army was executed for fleeing his barracks after reading a South Korean leaflet.

This woman lost eyesight of her left eye after getting a punched in her eye during an interrogation when she was repatriated back to North Korea in May 2005, after 8 years in China. On her second escape from North Korea, she suffered frostbite in her right foot, but could not afford to get medical help. (Picture taken in April 2006)

Many prisoners report that prison guards would engage in beatings so vicious that prisoners’ eyes mayfall out or leg bones may be exposed. Prisoners are also placed in solitary confinement in very small enclosures. A harsher variation of solitary confinement involves a “sweat box,” a prison cell so small that a person cannot fully stand or lie down within it. A prisoner sealed in a sweatbox is not allowed to move and is given almost no food, surviving only by eating bugs that crawl through the box. Prisoners often suffer frostbite and their bodies become covered with sores.

Escape attempts are punished by public execution, sometimes by hanging but more often by firing squad. The prisoners are compelled to assemble and witness the executions at close range. Virtually all former prisoners interviewed for this report witnessed numerous executions. Sometimes the prisoners were compelled to file by the corpse and throw stones at or strike the corpse. Former prisoners relate that they hated this gratuitous indignity, and held in contempt those prisoners who stoned the executed corpse with obvious force. And former prison guards reported that they also hated the public executions because the prisoners wailed and cried out in distress. The guards recounted that they feared the distraught prisoners might revolt and thus attended the public executions in force and heavily armed.

Others report that not only would the guards execute certain prisoners, but they would often mutilate the dead body or even require the prisoner witnesses to mutilate the body. Kang reports that after one hanging, the prisoner witnesses were required to hurl stones at the dead until the skin on the corpse’s face began coming off. Former prisoner Lee Young Kuk stated that he witnessed the execution of one attempted escapee, who was tied behind a car and dragged to death. The prisoner witnesses were then required to place their hands on the bloody body of the dead man. At this execution, a prisoner who witnessed the execution “shouted out against this atrocity.” The witness was shot and killed immediately.

Others report that not only would the guards execute certain prisoners, but they would often mutilate the dead body or even require the prisoner witnesses to mutilate the body. Kang reports that after one hanging, the prisoner witnesses were required to hurl stones at the dead until the skin on the corpse’s face began coming off. Former prisoner Lee Young Kuk stated that he witnessed the execution of one attempted escapee, who was tied behind a car and dragged to death. The prisoner witnesses were then required to place their hands on the bloody body of the dead man. At this execution, a prisoner who witnessed the execution “shouted out against this atrocity.” The witness was shot and killed immediately.

Women

Women represent the majority of North Koreans who flee into China. One of the reasons they cross the border is lack of sufficient food or the means of survival in their own country. For almost twenty years, famine has stalked North Korea. It reached its peak in the mid-1990s but remains a specter, and may reach crisis proportions again. Caused largely by government policies, combined with natural disasters, the famine of the 1990s killed and displaced millions of North Koreans. Women of the classes defined by the regime as politically disloyal became especially vulnerable when husbands and fathers died, and they began to flee to China in search of food and economic opportunities for themselves and their families. Unauthorized departure, however, is a crime in North Korea. Although seeking opportunities in China, they instead became victims of traffickers and victims of men in China who paid traffickers to purchase a North Korean “wife.”

Victims of trafficking

Women are so desperate in North Korea that they often turn to strangers and are deceived by traffickers, whom they trust to lead them into an unknown land. The women who cross the border, more often than male refugees, tend to do so in the company of others. Eighteen percent of those interviewed crossed the border with people whom they later came to realize were traffickers.

Most of the interviewed women came from the northeastern provinces of North Korea, presumably because of their proximity to the border, the severity of the famine in these provinces, and the regime’s disregard for people in this region. This area is known as the North Korean “Siberia,” where some people were sent if they were considered to be disloyal.

The severity of the famine in the northeastern provinces has often left women without husbands and fathers, and that factor has played a major role in their decision to leave. It is a consistent starting point in the life stories the majority of North Korean women told. In North Korea, after the death of their fathers or spouses, many of these women became homeless itinerant peddlers or scavengers until they crossed the border into China, risking their lives in the process.

Most of the interviewed women came from the northeastern provinces of North Korea, presumably because of their proximity to the border, the severity of the famine in these provinces, and the regime’s disregard for people in this region. This area is known as the North Korean “Siberia,” where some people were sent if they were considered to be disloyal.

The severity of the famine in the northeastern provinces has often left women without husbands and fathers, and that factor has played a major role in their decision to leave. It is a consistent starting point in the life stories the majority of North Korean women told. In North Korea, after the death of their fathers or spouses, many of these women became homeless itinerant peddlers or scavengers until they crossed the border into China, risking their lives in the process.

...

Sample testimonies from Lives for Sale

Marriage brokers provide North Korean women as wives, particularly in the rural areas where the historical preference for male babies has led over time to an acute shortage of marriage-age Chinese women. Having a Chinese husband, however, does not guarantee a North Korean woman’s safety, as she is still subject to repatriation. Moreover, women sold into Chinese families where they suffer physical, sexual, mental, and emotional abuse have very little recourse because of their status. Some women resort to prostitution as a source of income.19 In addition, North Korean women reportedly suffer abuse from Chinese guards along the border and North Korean officials upon repatriation.

Traffickers often prey upon the North Korean women near the border areas, and then sell them farther away, in rural areas of Jilin Province or other provinces such as Heilongjiang. In some cases, North Korean women are forced by their own relatives or neighbors to enter marriages with Chinese men in remote rural villages of China, and sometimes these relatives and neighbors receive payment in exchange. What seems an unforgivable violation of family responsibilities is often viewed locally as a pragmatic response to the dire situation facing North Korea’s escapees. Indeed, for many Koreans in China, forced marriages are considered a lesser evil compared to outright starvation and abject poverty. They would be unlikely to see the people they “help” as victims of trafficking or see themselves as traffickers; they certainly do not see themselves as violating international standards of human rights.

Denial of basic rights

The “marriages” the women enter, often through coercion, have no official standing in China and are given no legal protection. The women in these marriages are frequently “trapped,” unable to free themselves from arrangements in which they were sold for a price. They also live in fear of being returned to North Korea where they can expect incarceration, punishment, and even possible torture and death. Yet they are not permitted to prove they are political refugees or refugees sur place. Instead, they must bear exploitation and insecurity in China so as to avoid forced repatriation and punishment. Even when they are sold to partners who do not abuse them and raise families, they are still denied their basic rights. They and their children often have no legal status. Children conceived in China are usually not protected by the laws of either China or North Korea.

The children born to the marriages between North Korean women and Chinese men are often deprived of the basic rights they should have as a result of residence and Chinese nationality. Without hukou (residency certification), these children have less chance to attend school, or if they do, they do not receive textbooks like other students. Their academic performance is not officially registered with the national education authorities. This hinders their pursuit of higher education in the future. According to these interviews, 15 children out of a total of 42 had obtained hukou. These were registered under the child’s Chinese father’s name. Even this arrangement can be very expensive because local officials demand exceptionally high fees in such cases, which many of the parents can ill afford. Among the 15 children who had hukou, there were several recent cases from Jilin Province in which local authorities did not ask for bribes. Even though this is a positive development, 27 children out of 42 in Jilin and Heilongjiang Provinces, born in China and with Chinese citizens as fathers—therefore legitimate Chinese citizens—did not have legal documentation, because of their mothers’ irregular status.

Forced repatriation and severe punishment

China sends North Koreans back to North Korea without making an objective and informed decision as to whether they would be subject to persecution once they are returned to North Korea. The punishment and cruel treatment of North Koreans who are returned to North Korea is a matter of record, substantiated by numerous reports and testimony from those who have lived to escape to China again after repatriation. Yet China ignores this question of the treatment of North Koreans by North Korea when they are returned.

When escapees are returned by Chinese authorities to North Korea, they receive punishment in prison camps and detention facilities. This is the North Korean regime’s means of dealing with people who express their disloyalty with their feet, but it applies equally severely to those who held no particular political view and merely sought food, sustenance, and a better life. While China dismisses these people’s claim to being refugees—fleeing their homeland for political rather than economic reasons—North Korea sees it almost exclusively that way.

When escapees are returned by Chinese authorities to North Korea, they receive punishment in prison camps and detention facilities. This is the North Korean regime’s means of dealing with people who express their disloyalty with their feet, but it applies equally severely to those who held no particular political view and merely sought food, sustenance, and a better life. While China dismisses these people’s claim to being refugees—fleeing their homeland for political rather than economic reasons—North Korea sees it almost exclusively that way.

However, in reality, a significant number of North Koreans who cross the border into China qualify as asylum seekers—refugees with a well-founded fear of persecution should they remain in or return to their country of origin—under international law and hence are entitled to international protection. And, as has been long recognized and documented in multiple NGO reports, legal analyses, the reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in the DPRK, and most authoritatively by the Commission of Inquiry, virtually all North Koreans in China without entrance visas qualify as “refugees sur place”—persons who may not have left their country of origin out of a fear of persecution, but who would, irrespective of their reasons for leaving, face persecution if forcibly returned to their country of origin. Indeed, the Commission of Inquiry states, “[M]any such nationals of the Democratic Peoples [sic] Republic of Korea should be recognized as refugees fleeing persecution, or refugees sur place. They are thereby entitled to international protection.”48 For North Korean women without visas in China, brutal repression upon repatriation to North Korea is not a fear but—unless mitigated by bribery or exceedingly good luck—a reality.

Sometime after December 2008, Kyo-hwa-so No. 12 was expanded to include, for the first time, a women’s section that holds upwards of a thousand women. The expansion reflected a wave of arbitrary detention of thousands of North Korean women, a large majority of whom were imprisoned after being forcibly repatriated from China. The imprisonment of those women stands in violation of their right to leave their country of origin—a right guaranteed by conventions to which North Korea has acceded. Their forced return also is in contravention of international laws to which China has acceded that forbid the return of persons to countries where they will be persecuted. At Jongo-ri, these women political prisoners are subjected to forced labor under brutally harsh conditions.

In addition to this gross violation of internationally recognized human rights, other egregious violations include: systematic torture and beatings during investigation and interrogation immediately following forced repatriation; severe deprivation of food; the sexual humiliation of naked strip searches and the naked compulsory exercises (“squat thrusts” and “jumping-jacks”) to dislodge money or valuables that might be hidden in anal or vaginal cavities; and the barbaric practices of forced abortions or infanticides committed against repatriated pregnant North Korean women suspected of carrying babies fathered by Chinese men.

Related Texts: Lives for Sale: Personal Accounts of Women Fleeing North Korea to China and David Hawk, The Hidden Gulag IV: Gender Repression and Prisoner Disappearances (Washington, DC.: HRNK 2015)

Forced abortion and infanticide

If the Chinese man decides to return the pregnant woman to North Korea, however, her situation becomes far worse. It is reported that pregnant women returned to North Korea are forced to abort their pregnancies to prevent the birth of mixed-race North Korean children. A recent Korean Bar Association survey found that 57.7 percent of the defectors interviewed for the survey reported seeing or hearing that such pregnant women were forced to have abortions. While North Korean law states that pregnant women are not to be detained three months before and seven months after childbirth, in reality pregnant returnees from China are treated much more harshly than other returnees. Rather than receiving suspended sentences, pregnant women – when their babies are not forcibly aborted – are assigned hard labor to cause miscarriages.

Defectors report that if a woman is less than eight months pregnant, the fetus may be aborted through a syringe of salt water to the uterus. One repatriated defector describes an even more brutal form of abortion. Kim Myong Suk was 20 years old and five months pregnant when she was returned to North Korea from her “live-in” arrangement with a Chinese man. After forcing Kim’s sister to come to the prison to observe, the North Korean prison guard attempted to force Kim to abort her own pregnancy. When she refused, he began kicking her in the stomach repeatedly until Kim fell unconscious and the fetus, referred to by the guard only as “the Chink,” aborted.

If the woman is more than eight months pregnant, the baby is delivered and then killed or abandoned. Eyewitness accounts from defectors forced to act as midwives to pregnant repatriated North Korean women support this. In one instance, a fellow inmate/midwife was forced to give a pregnant woman a labor-inducing shot. After delivery, the baby was suffocated in front of the mother with a wet towel because “no half-Han [Chinese] babies would be tolerated.”

If the woman is more than eight months pregnant, the baby is delivered and then killed or abandoned. Eyewitness accounts from defectors forced to act as midwives to pregnant repatriated North Korean women support this. In one instance, a fellow inmate/midwife was forced to give a pregnant woman a labor-inducing shot. After delivery, the baby was suffocated in front of the mother with a wet towel because “no half-Han [Chinese] babies would be tolerated.”

Witness and Testimony: Former Detainee #24 Refouled at Sinuiju

Former Detainee # 24 was a sixty-six-year-old grandmother from Chulan-district, North Hamgyong province. In 1997, her children were starving, so she fled to China with her husband, who was a former soldier, and five of her children. Two of her children were caught crossing the border, but the rest of the family lived in China for three years. Two of the children who made it with her to China were later caught and repatriated to North Korea, and her husband eventually died of natural causes. Afterward, she lived with her granddaughter in Yanji until apprehended by Chinese police while visiting Dandong.

She was forcibly repatriated in a group of fifty North Koreans, some of whom were pregnant women, bound together by their wrists. They were taken, initially, for eighteen days to the Namin-dong Bo-wi-bu State Security Agency police ku-ryu-jang in Sinuiju. Initially, the police accused Former Detainee # 24 of being corrupted by capitalism in China. She convinced them that she had gone to China only for food, so she was sent for one month to the do-jip-kyulso in South Sinuiju run by the An-jeon-bu People’s Safety Agency police. Though she had heard that Kim Jong-il had recently said North Korean repatriates should not be treated harshly, there were beatings.

Detainees were fed the usual steamed corn, and as it was midsummer, most prisoners were sent out to work in the rice fields. This grandmother was too old and weak for such labor, and as she herself had had seven children, she was taken in the mornings to a nearby medical building to help care for the pregnant detainees. She helped deliver seven babies, some of whom were fullterm and others, injection-induced abortions. All of the babies were killed.

The first baby was born to a twenty-eightyear-old woman named Lim, who had been married to a Chinese man. The baby boy was born healthy and unusually large, owing to the mother’s ability to eat well during pregnancy in China. Former Detainee # 24 assisted in holding the baby’s head during delivery and then cut the umbilical cord. But when she started to hold the baby and wrap him in a blanket, a guard grabbed the newborn by one leg and threw him in a large, plastic-lined box. A doctor explained that since North Korea was short on food, the country should not have to feed the children of foreign fathers. When the box was full of babies, Former Detainee # 24 later learned, it was taken outside and buried.

She next helped deliver a baby to a woman named Kim, who also gave birth to a healthy full-term boy. As Former Detainee # 24 caressed the baby, it tried to suckle her finger. The guard again came over and yelled at her to put the baby in the box. As she stood up, the guard slapped her, chipping her tooth. The third baby she delivered was premature—the size of an ear of corn—and the fourth baby was even smaller. She gently laid those babies in the box. The next day she delivered three more premature babies and also put them in the box. The babies in the box gave her nightmares.

Two days later, the premature babies died but the two full-term baby boys were still alive. Even though their skin had turned yellow and their mouths blue, they still blinked their eyes. The agent came by, and seeing that two of the babies in the box were not dead yet, stabbed them with forceps at a soft spot in their skulls. Former Detainee # 24 says she then lost her self-control and started screaming at the agent, who kicked her so hard in the leg that she fainted. Deemed unsuitable for further hospital work, she was returned to the detention center until her release several weeks later.

Upon release, Former Detainee # 24 returned to China but was again caught and this time repatriated to Hoeryong. Separated from her granddaughter, she became hysterical and started singing Christian hymns that she had learned in China, and ranting against Kim Jong-il for the ruinous conditions that forced Koreans to have to flee their native villages—while God took care of Korean people in China. Fortunately, her guards regarded her as a crazy old woman, not an enemy of the regime. Indeed, they took pity on her, even reuniting her with her granddaughter and helping the two of them to again cross the Tumen River into China. This time, she met some South Korean Christian relief workers who helped her and her granddaughter to make the trek through China to Southeast Asia. She arrived in South Korea in March 2001.

She was forcibly repatriated in a group of fifty North Koreans, some of whom were pregnant women, bound together by their wrists. They were taken, initially, for eighteen days to the Namin-dong Bo-wi-bu State Security Agency police ku-ryu-jang in Sinuiju. Initially, the police accused Former Detainee # 24 of being corrupted by capitalism in China. She convinced them that she had gone to China only for food, so she was sent for one month to the do-jip-kyulso in South Sinuiju run by the An-jeon-bu People’s Safety Agency police. Though she had heard that Kim Jong-il had recently said North Korean repatriates should not be treated harshly, there were beatings.

Detainees were fed the usual steamed corn, and as it was midsummer, most prisoners were sent out to work in the rice fields. This grandmother was too old and weak for such labor, and as she herself had had seven children, she was taken in the mornings to a nearby medical building to help care for the pregnant detainees. She helped deliver seven babies, some of whom were fullterm and others, injection-induced abortions. All of the babies were killed.

The first baby was born to a twenty-eightyear-old woman named Lim, who had been married to a Chinese man. The baby boy was born healthy and unusually large, owing to the mother’s ability to eat well during pregnancy in China. Former Detainee # 24 assisted in holding the baby’s head during delivery and then cut the umbilical cord. But when she started to hold the baby and wrap him in a blanket, a guard grabbed the newborn by one leg and threw him in a large, plastic-lined box. A doctor explained that since North Korea was short on food, the country should not have to feed the children of foreign fathers. When the box was full of babies, Former Detainee # 24 later learned, it was taken outside and buried.

She next helped deliver a baby to a woman named Kim, who also gave birth to a healthy full-term boy. As Former Detainee # 24 caressed the baby, it tried to suckle her finger. The guard again came over and yelled at her to put the baby in the box. As she stood up, the guard slapped her, chipping her tooth. The third baby she delivered was premature—the size of an ear of corn—and the fourth baby was even smaller. She gently laid those babies in the box. The next day she delivered three more premature babies and also put them in the box. The babies in the box gave her nightmares.

Two days later, the premature babies died but the two full-term baby boys were still alive. Even though their skin had turned yellow and their mouths blue, they still blinked their eyes. The agent came by, and seeing that two of the babies in the box were not dead yet, stabbed them with forceps at a soft spot in their skulls. Former Detainee # 24 says she then lost her self-control and started screaming at the agent, who kicked her so hard in the leg that she fainted. Deemed unsuitable for further hospital work, she was returned to the detention center until her release several weeks later.

Upon release, Former Detainee # 24 returned to China but was again caught and this time repatriated to Hoeryong. Separated from her granddaughter, she became hysterical and started singing Christian hymns that she had learned in China, and ranting against Kim Jong-il for the ruinous conditions that forced Koreans to have to flee their native villages—while God took care of Korean people in China. Fortunately, her guards regarded her as a crazy old woman, not an enemy of the regime. Indeed, they took pity on her, even reuniting her with her granddaughter and helping the two of them to again cross the Tumen River into China. This time, she met some South Korean Christian relief workers who helped her and her granddaughter to make the trek through China to Southeast Asia. She arrived in South Korea in March 2001.

The first baby was born to a twenty-eightyear-old woman named Lim, who had been married to a Chinese man. The baby boy was born healthy and unusually large, owing to the mother’s ability to eat well during pregnancy in China. Former Detainee # 24 assisted in holding the baby’s head during delivery and then cut the umbilical cord. But when she started to hold the baby and wrap him in a blanket, a guard grabbed the newborn by one leg and threw him in a large, plastic-lined box. A doctor explained that since North Korea was short on food, the country should not have to feed the children of foreign fathers. When the box was full of babies, Former Detainee # 24 later learned, it was taken outside and buried.

She next helped deliver a baby to a woman named Kim, who also gave birth to a healthy full-term boy. As Former Detainee # 24 caressed the baby, it tried to suckle her finger. The guard again came over and yelled at her to put the baby in the box. As she stood up, the guard slapped her, chipping her tooth. The third baby she delivered was premature—the size of an ear of corn—and the fourth baby was even smaller. She gently laid those babies in the box. The next day she delivered three more premature babies and also put them in the box. The babies in the box gave her nightmares.

Two days later, the premature babies died but the two full-term baby boys were still alive. Even though their skin had turned yellow and their mouths blue, they still blinked their eyes. The agent came by, and seeing that two of the babies in the box were not dead yet, stabbed them with forceps at a soft spot in their skulls. Former Detainee # 24 says she then lost her self-control and started screaming at the agent, who kicked her so hard in the leg that she fainted. Deemed unsuitable for further hospital work, she was returned to the detention center until her release several weeks later.

She next helped deliver a baby to a woman named Kim, who also gave birth to a healthy full-term boy. As Former Detainee # 24 caressed the baby, it tried to suckle her finger. The guard again came over and yelled at her to put the baby in the box. As she stood up, the guard slapped her, chipping her tooth. The third baby she delivered was premature—the size of an ear of corn—and the fourth baby was even smaller. She gently laid those babies in the box. The next day she delivered three more premature babies and also put them in the box. The babies in the box gave her nightmares.

Two days later, the premature babies died but the two full-term baby boys were still alive. Even though their skin had turned yellow and their mouths blue, they still blinked their eyes. The agent came by, and seeing that two of the babies in the box were not dead yet, stabbed them with forceps at a soft spot in their skulls. Former Detainee # 24 says she then lost her self-control and started screaming at the agent, who kicked her so hard in the leg that she fainted. Deemed unsuitable for further hospital work, she was returned to the detention center until her release several weeks later.

Upon release, Former Detainee # 24 returned to China but was again caught and this time repatriated to Hoeryong. Separated from her granddaughter, she became hysterical and started singing Christian hymns that she had learned in China, and ranting against Kim Jong-il for the ruinous conditions that forced Koreans to have to flee their native villages—while God took care of Korean people in China. Fortunately, her guards regarded her as a crazy old woman, not an enemy of the regime. Indeed, they took pity on her, even reuniting her with her granddaughter and helping the two of them to again cross the Tumen River into China. This time, she met some South Korean Christian relief workers who helped her and her granddaughter to make the trek through China to Southeast Asia. She arrived in South Korea in March 2001. (From David Hawk, The Hidden Gulag Second Edition (Washington, DC.: HRNK, 2012) and Failure to Protect: A Call for the UN Security Council to Act in North Korea (Washington, DC.: HRNK 2006))

Disappeared Persons

North Korea’s policy of abducting foreign citizens dates back to the earliest days of the regime, and to policy decisions made by North Korea’s founder Kim Il- sung himself. Those abducted came from widely diverse backgrounds, numerous nationalities, both genders, and all ages, and were taken from places as far away as London, Copenhagen, Zagreb, Beirut, Hong Kong, and China, in addition to Japan.

|

Kim Yong-nam (R) ad Megumi Yokota (L)

Practices that North Korea has engaged in when abducting foreign nationals:

|

Initially, people were abducted from South Korea during the Korean War. Soon afterwards, Koreans were lured from Japan and held against their will in North Korea. A decade later, children of North Korean agents were kidnapped apparently to blackmail their parents. Starting in the late 1970s, foreigners who could teach North Korean operatives to infiltrate targeted countries were brought to North Korea and forced to teach spies. Since then, people in China who assist North Korean refugees have been targeted and taken.

... |

Related Texts: Taken!

The double disappearances of former prisoners

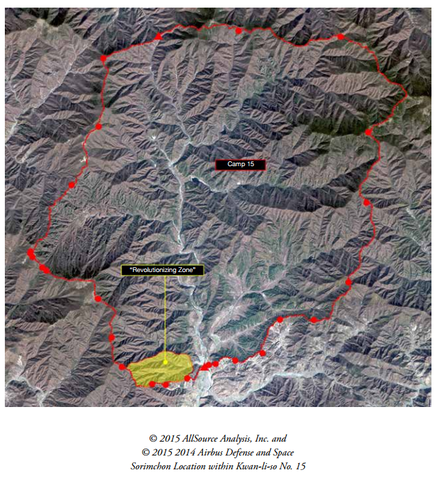

Sorimchon, a small hyeok-myong-hwa-koo-yeok (“revolutionizing processing zone”), was established in or around 1999 in the southern corner of Camp 15. Camp 15 is 365 square kilometers and is the most well-documented kwan-li-so political prison camp in North Korea.

|

In late 2014, satellite photographs of Kwan-li-so No. 15, available in an HRNK and AllSource Analysis (ASA) report, showed that the buildings within the Sorimchon area of the prison camp had been demolished. In fact, over the last fifty years, North Korea’s prison camps have undergone a continuing series of consolidations, during which time a number of camps have been closed and/or relocated. In all of these consolidations, closures, and relocations, the world outside North Korea has practically no knowledge of the fates or whereabouts of the former and present prisoners.

|

Pictured above: Camp 15

|

North Koreans are doubly disappeared: first, in their deportation without trial or judicial process into incommunicado detention; and second, in regards to their fate and whereabouts following the demolition of the Sorimchon section of Camp 15.

of the Sorimchon "Revolutionizing Zone" within Camp 15 Yodok

In the case of the small, demolished section of Camp 15, the names of many of the persons formerly imprisoned there have been recorded and reported by other former prisoners, especially Mr. Jung [Gwang-il]. These persons, like all prisoners in the kwan-li-so political penal labor colonies, were deprived of their liberty without any of the formal judicial processes outlined in North Korea’s criminal law and criminal procedure code and subjected to forced labor under conditions so harsh as to result in high rates of death in detention. The Commission of Inquiry determined that the operation of these prison camps constitutes crimes against humanity.

Of the 181 former prisoners [...], two were executed and one died from torture and beatings. Twenty-three died of malnutrition or starvation. Five were taken away, and their fate is unknown. Fifteen are known to be alive. Several are in South Korea. One is believed to be in the United States. Seven are believed to have been personally ordered released by Kim Jong-il. The status, fates, and whereabouts of 121 are completely unknown.

The missing persons from the Sorimchon section of Camp 15 are doubly disappeared: first, into the prison camp, and again, upon the demolition of the section of the camp where they were subjected to forced labor and political “re-education.”

In the case of the small, demolished section of Camp 15, the names of many of the persons formerly imprisoned there have been recorded and reported by other former prisoners, especially Mr. Jung [Gwang-il]. These persons, like all prisoners in the kwan-li-so political penal labor colonies, were deprived of their liberty without any of the formal judicial processes outlined in North Korea’s criminal law and criminal procedure code and subjected to forced labor under conditions so harsh as to result in high rates of death in detention. The Commission of Inquiry determined that the operation of these prison camps constitutes crimes against humanity.

Of the 181 former prisoners [...], two were executed and one died from torture and beatings. Twenty-three died of malnutrition or starvation. Five were taken away, and their fate is unknown. Fifteen are known to be alive. Several are in South Korea. One is believed to be in the United States. Seven are believed to have been personally ordered released by Kim Jong-il. The status, fates, and whereabouts of 121 are completely unknown.

The missing persons from the Sorimchon section of Camp 15 are doubly disappeared: first, into the prison camp, and again, upon the demolition of the section of the camp where they were subjected to forced labor and political “re-education.”

...

This list of Sorimchon prisoners is based on Mr. Jung Gwang-il's three-year imprisonment in the Sorimchon section of Kwan-li-so No. 15 Yodok and his impressive memory. Mr. Jung is the Founder and Executive Director of No Chain: The Association of North Korean Political Victims and Their Families.

International human rights law and customary law

It is very likely that mass graves exist in or near North Korea’s political prison camps. While there is no strict legal definition of mass graves, the term connotes a place where multiple bodies are compiled. Testimony by former prisoners indicates that prisoners buried in mass graves had their limbs broken to reduce their size, or were tightly wrapped, and then were dumped carelessly, cruelly into shallow, unmarked graves in the nearby mountains of the camps. Other accounts recall bodies being cremated. Continued monitoring and identification of suspected mass burial sites in North Korea is critical not only for uncovering atrocities, but also for ensuring accountability.

The most basic and fundamental human right denied in these camps is the right to life. “[T]he right not to be arbitrarily deprived of life ‘is the supreme law of human beings. It follows that the deprivation of life by state authorities is a very serious matter.’” North Korea has a legal obligation under international human rights law to respect and protect the right to life, “including when such persons are held in custody.” According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), “The duty to respect and ensure the right to life implies that no one may be arbitrarily deprived of his or her life.” In the case of North Korea’s detention facilities, the right to life is blatantly disregarded and violated. The ICRC report also specifies an obligation to investigate deaths in custody:

The most basic and fundamental human right denied in these camps is the right to life. “[T]he right not to be arbitrarily deprived of life ‘is the supreme law of human beings. It follows that the deprivation of life by state authorities is a very serious matter.’” North Korea has a legal obligation under international human rights law to respect and protect the right to life, “including when such persons are held in custody.” According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), “The duty to respect and ensure the right to life implies that no one may be arbitrarily deprived of his or her life.” In the case of North Korea’s detention facilities, the right to life is blatantly disregarded and violated. The ICRC report also specifies an obligation to investigate deaths in custody:

Under human rights law, the prohibition against the arbitrary deprivation of life, read in conjunction with the general obligation to respect and ensure human rights within the State’s jurisdiction, has been interpreted as imposing by implication an obligation to investigate alleged violations of the right to life. This obligation is put into effect whenever a detainee—without injuries when taken into custody—is injured or has died

Finally, as a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), North Korea has an obligation “[t]o ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.” As The Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions states, “[t]here shall be thorough, prompt and impartial investigation of all suspected cases of extra- legal, arbitrary and summary executions, including cases where complaints by relatives or other reliable reports suggest unnatural death.” Family members of these victims have a right to an investigation and may be entitled to reparations. Specifically, the UN Human Rights Committee “found that systematic failure to inform families of the burial sites of executed prisoners violates Article 7 of the ICCPR.”