|

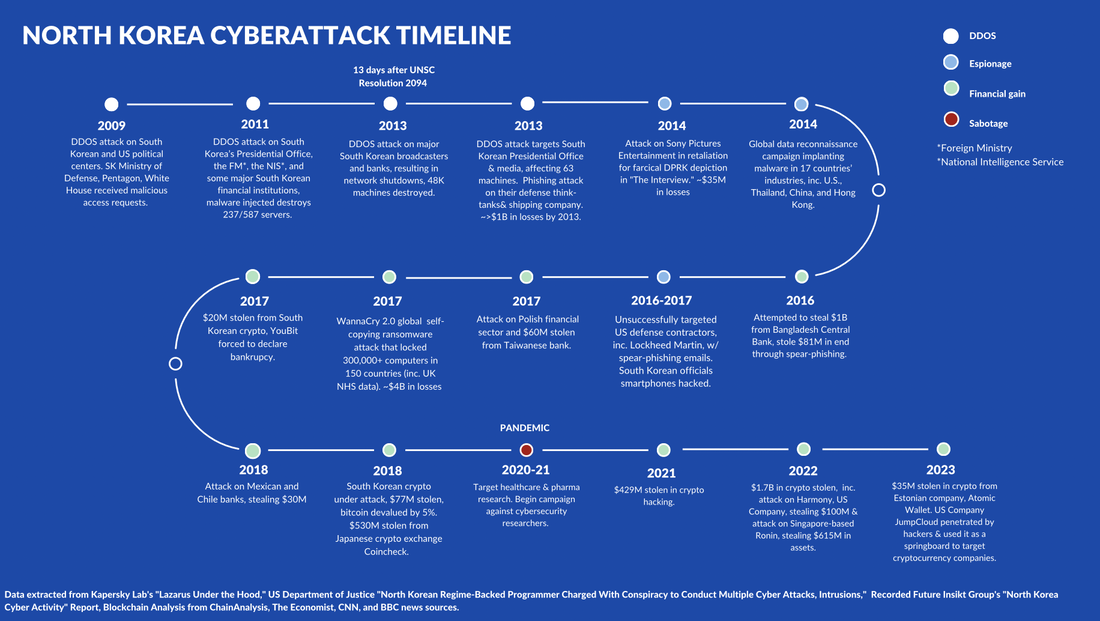

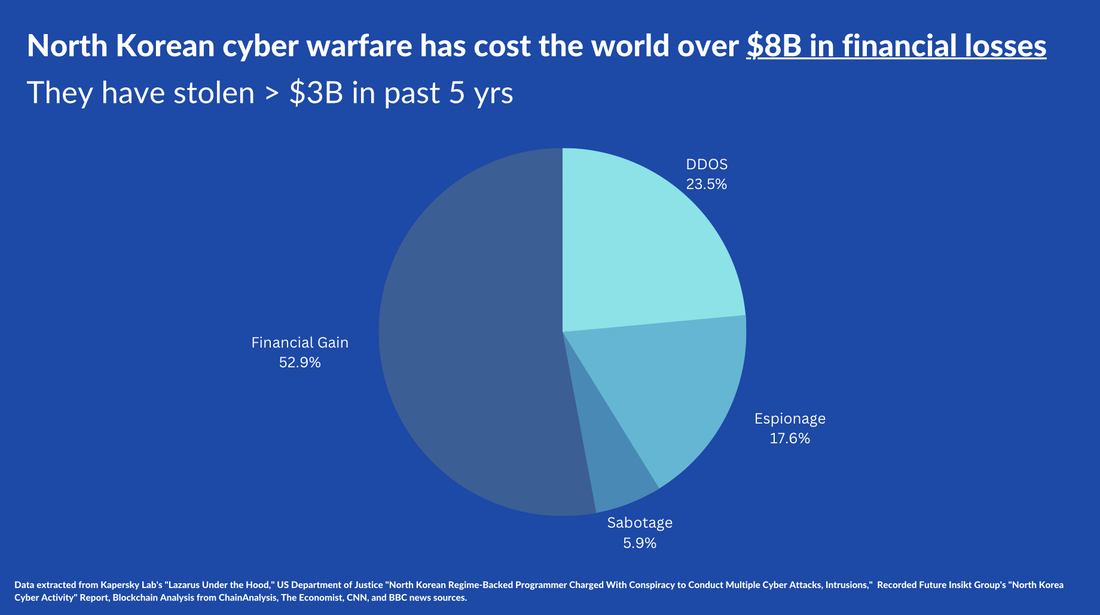

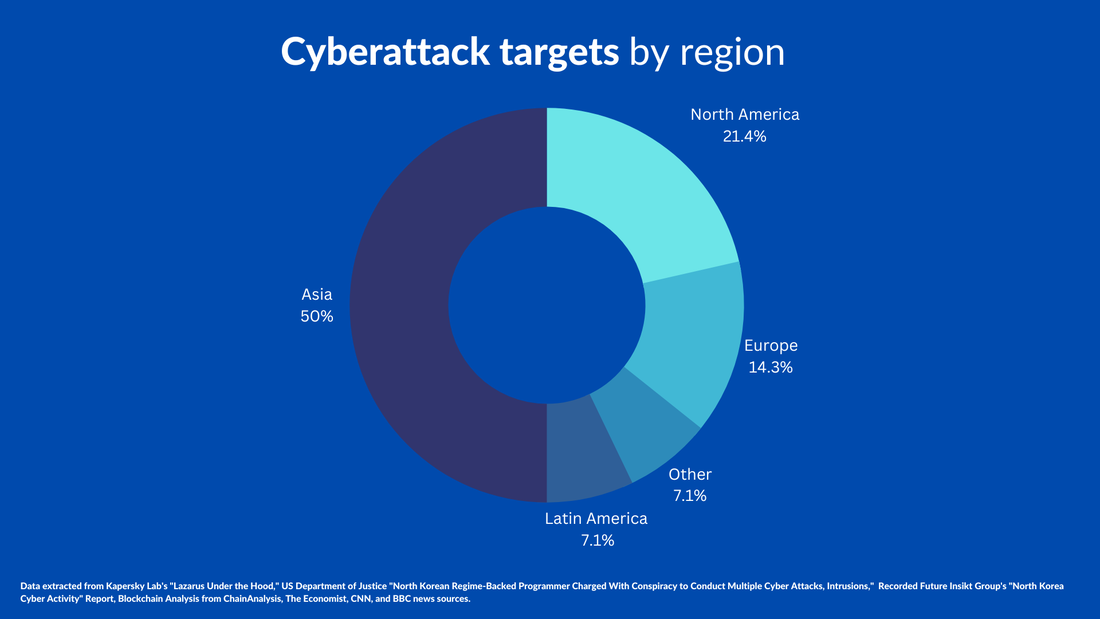

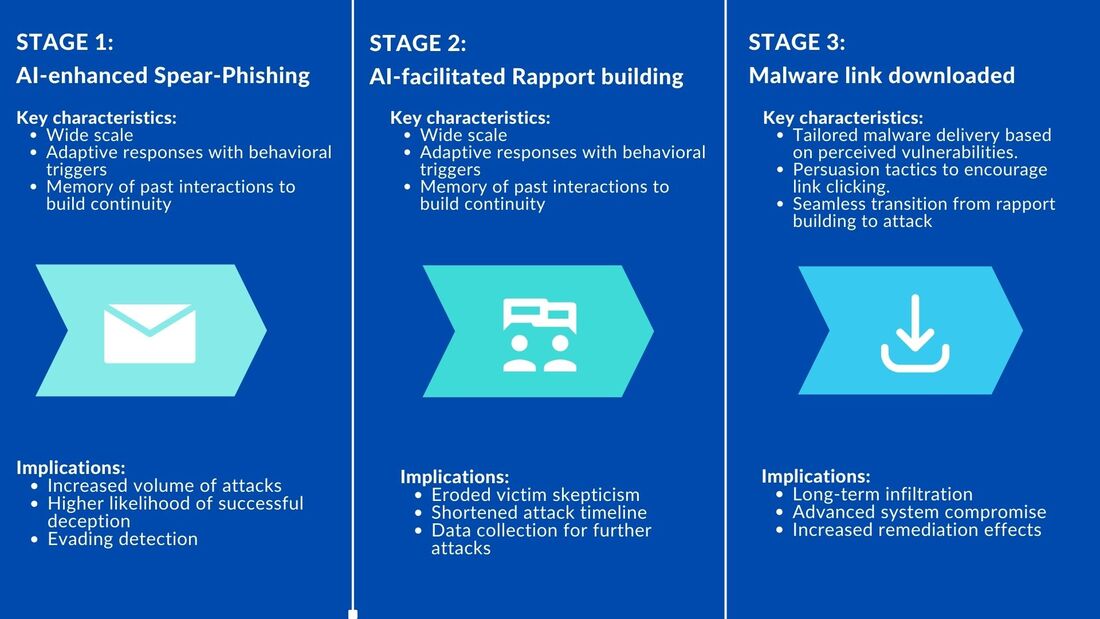

By Tiana Lakhani, HRNK Research Intern Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research At the 2016 World Economic Forum, a landmark term was coined—the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” This conceptual framework has grown to symbolize a new era, one that is characterized by rapid technological advancements and their profound implications on the global socio-economic and political landscapes. Artificial Intelligence (AI), as a cornerstone of this revolution, has been rapidly adopted globally, prompting urgent discussions about potential threats and opportunities. In the context of these discussions, one nation draws peculiar attention: North Korea, universally recognized as the most isolated and enigmatic country in the world. The question that arises is, how does North Korea, cloaked in secrecy and governed by a tightly controlled regime, engage with this global phenomenon? Is the inclusion of AI into North Korea's cyber strategies a futuristic aspiration, or could it be an emerging reality hidden in the obscurity of this enigmatic state? The prospect of AI playing a role in North Korea's cyber landscape might not be as distant as it appears. The Korean Peninsula has long been stuck in a military impasse, a situation that is decidedly unfavorable for North Korea. Faced with a desire to alter this status quo, yet constrained by the high risks associated with conventional military methods, North Korea has turned to cyber capabilities as an alternative. This strategic pivot represents an asymmetric strategy that allows North Korea to bypass the deadlock via a path of lesser resistance, defined by low-intensity, low-cost, and low-risk operations. This provides an effective way of circumventing harsh sanctions that target sources of funding for their missile and nuclear programs. Experts believe that North Korea has fostered a robust organizational structure capable of executing consequential cyber operations, as demonstrated by their alleged involvement in the Sony attack in 2014. Contrary to what one might expect from such a secluded nation, North Korea boasts a surprisingly strong technological base that reinforces its cyber capabilities. AI has the potential to augment spear-phishing campaigns by automating attacks, tailoring deceptive messages, and creating counterfeit identities, strengthening cyberattack capabilities. This technology could be attractive for North Korea to leverage, as it represents an extension of their existing cyber strategies, enabling more sophisticated and targeted approaches for financial gain. This could affect the right to privacy on a global scale. However, it is essential to recognize that the application of AI in this context is still in the early stages, with limitations in scalability and effectiveness. By investigating this intersection of technology and cybersecurity, this essay concludes that careful monitoring of advancements, encouraging international cooperation, applying further pressure on complicit nations such as China, and utilizing “naming-and-shaming” strategies are effective in combatting these emerging threats. This essay contributes to a measured understanding of the evolving landscape of cyber warfare and underline the importance of a coordinated, global response. Technological Landscape and Cyberattacks Pre-AI Integration Image A reveals a discernible shift in strategic focus in the evolution of North Korea’s cyber activities. The period between 2009 and 2013 was predominantly characterized by the deployment of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, which are disruptive attacks that paralyze computer networks. There was a strategic transition from 2014 to 2017, where North Korean cyber operations exhibited a mix of espionage and financial gain objectives. However, after 2017, there was a dramatic refocusing towards financial gain. This shift coincides with a period of severe economic contraction in North Korea, with 2020 marking the most significant shrinkage in the country’s economy in 23 years. This demonstrates a strategic pivot from the deployment of DDoS attacks towards cyber operations aimed explicitly at financial gain. This underscores maturation in North Korean cyber strategies and sheds light on the regime’s interest in these activities as a low-risk revenue stream in the coming years. The sheer financial impact of North Korea's cyber warfare activities underscores its urgency as a global concern, as revealed in Image B. Their cyber operations have cost the international community staggering sums, and the range of their operations has proven remarkable. Yet, these figures only begin to scratch the surface of their impact, failing to account for the equally significant, yet intangible, costs associated with data breaches, data theft, and the ensuing erosion of trust in digital systems. Beyond financial institutions and corporate entities, North Korea's hacking operations have breached personal devices, thereby gaining unauthorized access to private information, and have even infiltrated healthcare systems, as evidenced by an incident involving the U.K.’s National Health Service. Such transgressions not only threaten our individual privacy and security, but also have wider implications for the integrity and resilience of our increasingly digital society. Furthermore, the potential integration of AI into North Korea's cyber arsenal could significantly exacerbate these threats. AI technologies can automate and scale hacking activities, thereby augmenting their speed, sophistication, and impact. The fusion of AI with cyber warfare capabilities hence stands to dramatically inflate both the frequency and severity of cyberattacks, rendering this issue all the more pressing. In the face of such a multi-faceted threat, a comprehensive, globally coordinated response is warranted and required. An analysis of North Korea's cyberattack strategies reveals discernible patterns and priorities that vary across different geographic regions, as showcased in Image C. South Korea, for instance, absorbs the majority of North Korea’s malicious cyber activity in Asia, accounting for half of all such incidents. The character of these incursions in Europe is more differentiated. North Korea directly targets the financial sectors of less developed nations like Poland, while it seeks to exploit valuable data in more advanced countries, such as the U.K., as evidenced by the 2017 ransomware attack. The United States has experienced a notable shift in North Korean cyber aggression. Initially, North Korea's activities, starting in 2009, were primarily aimed at disrupting political systems, as revealed in Image A. However, there has been a reorientation towards financial gain in recent years, with U.S. companies becoming increasingly targeted. Furthermore, North Korea has found a profitable avenue in cryptocurrencies, amplifying their gain from cyber operations. Other developing nations like Chile and Mexico have also suffered significant financial losses, estimated at around $30 million. The potential integration of AI into North Korea's cyber capabilities is a worrisome prospect. AI could amplify the reach, scale, and sophistication of these attacks, increasing both the number of targets and the severity of damage. Given North Korea's evolving strategies and targets, the integration of AI would likely enable them to infiltrate more secure systems, automate complex attacks, and ultimately exacerbate the global threat they pose. Post-AI Weaponization: Scenario Analysis Stage 1: Spear-phishing Stage 2: Luring – “building a rapport” Stage 3: Malware link is sent and downloaded by recipient Spear-phishing serves as the “Trojan Horse” for North Korean hackers, granting them the initial access necessary to launch DDoS attacks, engage in espionage, or enact acts of sabotage for financial gain. Upon closer examination, two principal strategies emerge wherein the integration of AI could significantly enhance the efficacy of these nefarious activities: the automation of attacks and the creation of counterfeit personas. By leveraging AI's autonomous problem-solving skills, as evidenced by Large Language Models (LLMs) and the Algorithm Distillation (AD) technique, North Korean attackers could automate the process of sending deceptive emails or messages. This could involve a complex task decomposition where the AI breaks down the large task of sending spear-phishing emails into smaller, manageable subgoals, making the attack process more efficient and widespread. Furthermore, AI's ability for self-reflection and learning from past experiences could be exploited to refine and improve attack strategies based on past successes or failures, making future attacks more effective. This could also involve using AD to train the AI systems more efficiently in various phishing tactics, allowing it to adapt and improve its strategies over time by refining tactics based on these learning histories and retaining important knowledge for long-term use in North Korea’s cyber strategies. Noted security expert Bruce Schneier's recent proof-of-concept research unveils an innovative threat model that could be leveraged by North Korea given their history in producing wide scale attacks like WannaCry 2.0. This model highlights vulnerabilities in AI systems, including LLMs. This emerging form of automated attack is indicative of the evolution in cyber threats, where unsuspecting users unknowingly trigger deceptive commands embedded in multimedia content such as images or sound clips. When queried about these manipulated inputs, an AI chatbot either unveils the hidden prompt or follows the concealed instructions, sparking a range of harmful consequences. This is critical. It essentially means that attackers can manipulate systems like ChatGPT into performing actions that it normally should not, like executing harmful commands. Moreover, these strings can transfer to many closed-source, publicly-available chatbots, significantly amplifying the risk across widely used commercial models. Lastly, another study reveals how OpenAI’s GPT-3 and AI as-a-service products can automate spear-phishing by creating highly targeted emails. By employing machine learning and personality analysis, the study was able to generate phishing emails that were tailored to specific individual traits and backgrounds, resulting in messages that sounded “weirdly human.” Given that grammar errors often betray North Korean hackers, AI's capability to correct such mistakes, along with its inclusion of precise regional details like local laws, amplifies the authenticity of phishing endeavors. Despite the small sample size and the homogenous nature of the study, the research succeeded in demonstrating the potential of AI to outperform human-composed messages in spear phishing. This approach's success in creating convincing, individualized phishing emails highlights the alarming potential for AI to be used for malicious purposes in North Korea’s state-sponsored cyberattacks, and underscores the need for further exploration and defense strategies. Beyond automation, the rise of generative AI platforms such as Generated.Photos and ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com poses a complex threat. These platforms that craft convincing fake personas are more than a novel tech curiosity. They are a potential cybersecurity nightmare. For as little as $2.99, these lifelike avatars can be tweaked and animated, lending authenticity to fictitious profiles. While useful for legitimate purposes like video game development, North Korean hackers could exploit these tools to fabricate deepfakes for fraudulent schemes. A study even revealed that fake faces created by AI are considered more trustworthy than images of real people. Imagine a world where phishing scams and social engineering attacks are not perpetrated by crude caricatures, but instead by AI-generated personas that are indistinguishable from real people. This is a formidable gateway that North Korea could exploit, turning ingenuity into a clandestine weapon for cyber subterfuge. The potential implications extend beyond visual representations. AI-generated software is also capable of impersonating voices, a technique that has already been utilized in isolated fraudulent activities. For example, scammers were reported to have impersonated a chief executive’s voice to facilitate a fraudulent transfer of $243,000 from a U.K.-based energy firm, as detailed in the Wall Street Journal. While these developments and their implications underscore the growing complexity of cybersecurity in the age of AI, it is vital to approach the subject from a balanced perspective. The potential risks, though significant, must be weighed against the current state of technology, its accessibility, and the existing safeguards. The interplay of these factors should guide ongoing research, policy considerations, and risk management strategies to ensure that technologies are not exploited for malicious ends. Next Steps The immediate focus should be on discerning insights from previous cyberattacks to prepare for the potential of AI-integrated cyber warfare. As indicated earlier, North Korea's motivations for pursuing cyberattacks, particularly for financial gain, appear to be growing in the context of their economic challenges and an expanding nuclear program. Background discussions with experts in the field, including Jenny Jun, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, sheds further light on the unique characteristics and concerns associated with North Korea's approach to cyber warfare. Jun stated, What makes me most worried about North Korea’s cyber threat is that they are sometimes not afraid to launch operations that are brazen and destructive with a singular determination to achieve the task at hand, even if it means that their operations are less discreet as a result. For example, in 2018 North Korea reportedly destroyed 9,000 workstations and 500 servers through a wiper attack on Banco de Chile, in order to obfuscate investigation of a $10 million fraudulent SWIFT 1 transaction in a bank heist. Not only do such techniques increase the extent of the victim’s damage, they are indicative of a certain North Korean mindset that has a disregard for diplomatic consequences as a result of attribution. Her insights allow us to understand the urgency of understanding North Korea's approach and their behavior in the context of these advancements in AI. It is crucial to develop robust countermeasures to safeguard against an evolving and potentially more dangerous threat landscape. The right to privacy stands as a critical human rights concern for the foreseeable future. North Korea's conduct in cyber warfare clearly violates protection against interference with privacy in Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which North Korea has ratified. Further, the enigmatic nature of cyberattacks renders attribution highly elusive. Dr. Ethan Hee-Seok Shin, a legal analyst at Seoul-based NGO Transitional Justice Working Group, elucidated this paradox, noting the complex challenges of identifying culprits and attributing responsibility in cyber warfare. He stated, A hacker squad distributing malware has deniability that a military unit lobbing artillery shells over the border does not. The work of AI-curated identities presents a further legal conundrum since, to quote the Nuremberg judgment, crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced. Who should be put on trial? Clearly not the abstract AI-curated identities, but then their human creators or operators could plead that they never ordered an attack on a particular target. Shin's insights cast a stark light on the legal quagmire that defines cyber warfare. International law's enforcement becomes a Herculean task, especially against a nation like North Korea, which has repeatedly flouted agreements it has ratified and dismissed international norms. It is vital to recognize that the majority of North Korean hackers operate beyond their own borders, particularly in nations like China. This presents a perhaps underutilized strategic angle: the potential to exert diplomatic pressure on countries where these nefarious activities are being orchestrated, and imposing targeted sanctions against responsible individuals and entities in these countries. Shin, who recently testified at a congressional hearing, shed light on this issue. The hearing addressed China's complicity in North Korea's misdeeds, a subject that could create substantial discomfort in Beijing, as the Chinese government is keenly aware of its international reputation. Shin noted, "Beijing's entanglement in these activities places them in a precarious position; they do not wish to suffer reputationally due to their association with North Korea's wrongdoings." He further emphasized the necessity of collaborating with like-minded governments committed to halting these cyberattacks. While acknowledging the complexity of this endeavor, he asserts, “it is important to work with other cooperative governments who have interest to stop the cyberattacks from happening. It is not going to be easy, but it is something we can try.” As we traverse this complex landscape, it is evident that forming a united front is not just a choice, but a necessity. The ever-evolving tapestry of North Korea's cyber strategies stands as a testament to the urgency of innovative responses. By bringing into focus an internationally coordinated effort and a strategic emphasis on those who are complicit, like-minded nations can seek a path towards dismantling the legal and geopolitical challenges that arise. This approach underscores the importance of collective resilience and adaptability, which are critical for shaping the contours of a safer, more secure cyberspace. Tiana Lakhani is a rising junior at Stanford University, majoring in International Relations and planning for a prospective MA in East Asian Studies in her senior year.

0 Comments

By Elizabeth Jean H. Kim, HRNK Research Intern

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research The demographics of North Korean escapees reveals a notable gender gap between men and women.[1] Previous studies have already addressed how gender roles have influenced individuals’ decision to escape North Korea since the great famine in the late 1990s. However, the question of “What causes North Korean women to escape in much larger numbers than men?” requires further explanation. This article examines the gendered defection of North Koreans. Given my first-hand experiences as a North Korean refugee and hope to be a scholar of North Korean human rights issues, I am focusing on this research on how the gendered defection of North Koreans is related to structural factors and economic developments, including the rise of market activity during and after the famine of the 1990s. I also emphasize the pull factor of the gender imbalance in China, which led to the large-scale trafficking of North Korean women. Lastly, I argue that escapes from North Korea in recent years have been primarily influenced by family ties and social networks, sometimes involving escapees who have already resettled in South Korea. Structural Factors North Korea’s socialist system structurally segregates gender. Men are required to serve in the military for ten years, starting at the age of 17. During high school, all of my male classmates registered and took regular physical examinations under the local military mobilization department. After graduating, the majority entered military service. Only a few of my male classmates were waived from the military requirements, including those with physical disabilities, those who enrolled in college after being identified for their academic talent, and those with “unfavorable” family backgrounds due to guilt-by-association. On the other hand, only three of my female classmates—those over 5.2 feet (158 cm) tall—were qualified to serve in the military for eight years. Although I was also qualified for military service, I enrolled in college instead. Due to chronic malnutrition and forced labor from a very young age, the average height of North Korean women is smaller than South Korean women. According to a 2016 study, the difference is 3.3cm (162.3 cm vs. 159cm).[2] While North Korean men are tightly controlled under the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) in the public sphere, North Korean women mostly remain in the domestic sphere. If girls do not qualify for military recruitment or college enrollment, they automatically became members of the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League in workplaces and institutions, including textile factories and farms. Once these women get married, they are transferred from the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League to the Women’s Union, an official organization that is used for mobilizing North Korean women. Women remain members of the Women’s Union for life. Past Defections and the Impact of Marketization After the collapse of the socialist system and Kim Il-sung’s death in 1994, the public distribution system no longer provided enough goods or necessities for North Koreans.[3] The Kim Jong-il regime proclaimed the “Military First” ideology to reinforce national security. The regime continually recruited North Korean men into the military. Meanwhile, the KWP and the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League strictly controlled men who were disqualified from military service by making them work at industrialized facilities with almost no pay. At the time, my father’s official monthly salary was very low. We could barely buy 2 lb of pork, despite his relatively high position in a government-assigned job. My mom did not even calculate his salary in our family finances. Instead, we considered it as “free money.” One escapee I talked to told me that he had been a dam repairman in Ryanggang Province. He received 1,400 North Korean won per month for his work. “There was nothing I could do with this money, maybe I could buy 0.2 kilograms of rice,” he recalled. This reveals a glimpse of just how low official salaries were at the time. They were not enough for male North Korean workers to provide for their family’s basic needs. Instead, women sustained their families through economic activity at local markets, smuggling, developing private farms, and cultivating herbs. This economic activity had a direct influence on migration patterns. Female escapees who lived near the Chinese border (North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces) were more likely to escape due to the emergence of new economic activity. North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces are the focal points of illegal trade with China. According to South Korea’s Ministry of Unification, almost 80% of the 24,389 female North Korean escapees who have resettled in South Korea are from these two provinces.[4] During my nearly two-year confinement in a refugee camp during my journey to the United States, I met many female escapees from North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces. I was familiar with their northern accent, and I quickly noticed details about their background. Some were from the same town near the border with China, and some even went to the same school before leaving North Korea. Most of them left their hometown to seek economic opportunities or to pursue their personal aspirations for a better life, but they became victims of human trafficking in China. I also met female North Korean escapees from Pyongan Province. One of these women, P, had been born and raised in Pyongyang. After the public distribution system collapsed, however, she went to her aunt’s house in Musan County in North Hamgyong Province to make a living through smuggling. However, a woman in her aunt’s neighborhood approached her to suggest going to China to make money, luring her into sex trafficking and forced marriage with a Chinese man. During and immediately after the famine of the 1990s, fraud and lack of awareness also contributed to gendered defection. Living in a confined, overcrowded room in dire conditions with insufficient food at the refugee camp, I built rapport with many female North Korean refugees. I observed that the majority of North Korean women, especially those who escaped in the late 1990s and early 2000s, were tricked by their neighbors, friends, and sometimes even relatives into going to China, where they became victims of human trafficking. This has also been documented by researchers. For example, one North Korean escapee went to China with her friend and her friend’s father to try and find her two sisters, who had already escaped to China and had been forced to marry Chinese men. However, after crossing the Tumen River, her friend’s father sold her to a Chinese man instead.[5] After the famine, China became North Korea’s most significant trade partner. Chinese companies collected natural resources from North Korea, like wood, medicinal herbs, and mineral resources. Those who live near the border with China rely on exchanging natural resources and other trade to make a living. One such North Korean escapee, C, went to collect blueberries near Baekdu Mountain with her friends, but ended up reaching a Chinese village by accident. “I did not know how to go back home,” she told me. Lacking information or reliable social networks, North Korean women who arrive in China often become victims of trafficking. According to one estimate, approximately 70% to 80% of North Korean women who cross into China fall victim to human trafficking.[6] Pull Factors Gendered North Korean defection is directly reflected in pull factors on the Chinese side. The gender imbalance resulting from decades of enforcing the “one-child policy,” combined with traditional gender norms, created a “demand” for North Korean women, who are sold into marriage and kept in captivity. In contrast, the pull factor of North Korean men to China is relatively low. North Korean men find work on hidden farms or in the lumber industry in northern China through an underground labor market. They are severely exploited by their Korean-Chinese employers. Mr. C, who joined our group of escapees in Shenyang after being released from a long-term prison labor facility in North Korea, said that he crossed the border into China to earn money to support his family. Once he arrived in China, he connected with his friend, who was already working in a lumber facility in Changchun. The living and working conditions there were horrific. Even worse, his employer was unwilling to pay the North Korean workers and reported them to the police. The workers were subsequently repatriated to North Korea. Another male escapee pointed out to me that “we knew that we would not be welcome in China even if we escaped there, and there is nothing we can really do.” Contemporary Trends In recent years, escapes from North Korea are more likely to be related to social networks and human capital. Even after Kim Jong-un further tightened border security upon coming to power, there was still a gender imbalance among escapees who arrived in South Korea. The number of North Korean women who escaped to South Korea after living in China is relatively higher than those who directly crossed the border from North Korea. NGOs and South Korean missionaries play an important role here. I was rescued by a South Korean missionary organization while I was in China. With their help and protection, I successfully reached out to a third country where I could claim my status as a refugee. In my group, six out of eight had been rescued by the same organization from China, and only two had recently left North Korea with help from family members who had already resettled in South Korea. I learned in the refugee camp that there were large numbers of female North Korean escapees who had been rescued by NGOs and mission organizations, many of them from China. Nevertheless, the gender gap among escapees has shrunk since 2021 due to the regime’s COVID-19 restrictions. The small number of escapees who arrived during the pandemic could do so thanks to the help of family members and other social networks, making it easier to navigate their journey to South Korea. It is likely that these recent escapees had been trapped in China for a while, and could sustain themselves with the support of family members who were already living in South Korea. By contrast, it is now difficult for North Korean women in China to escape unless they have family members or relatives who can help. Due to advanced surveillance technology and restrictions on movement, there are greater risks in rescuing North Korean women from China. Moreover, the cost is much higher than before. In the case of K, a female escapee who arrived in South Korea in 2020, both of her parents had already been living in South Korea for a decade. With her parents’ support, K was successfully rescued from North Korea and arrived in South Korea in the middle of the pandemic. Concluding Remarks The decision to escape from North Korea must be examined from multiple perspectives, including structural factors, economic changes, the power of women’s economic contribution, regional mobility, and the pull factor resulting from the gender imbalance in China. During and shortly after the famine of the 1990s, gendered defection directly reflected institutionalized gender separation within North Korea. Economic devastation pushed North Korean women, mostly from North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces, to go to China to seek economic opportunities or to achieve their personal aspirations. However, upon arriving in China, North Korean women were often lured into sex trafficking networks through fraud and deception. Moreover, the gendered defection of North Koreans must be understood with reference to the gender imbalance in China. It is in this context that many North Korean women were sold to poor rural Chinese men. In recent years, escapes from North Korea have been more closely related to family ties and social networks. The latter includes NGOs and religious organizations. Overall, the number of escapees has drastically dropped over the past couple of years. To rescue North Korean women in China who have fallen victim to trafficking, more NGOs and international humanitarian organizations must pay attention to these issues as serious violations of human rights. The international community must pressure China to take responsibility for and assist trafficked North Korean women. China can take tangible steps, such as providing them with a legal basis for staying in China and facilitating humanitarian protection. For North Koreans who newly escape to China, the Chinese government should create a new category of asylum seekers and allow a temporary immigration status instead forcibly repatriating them. Elizabeth Jean H. Kim (pseudonym) is a North Korean refugee student who studied Sociology and International Relations at the University of Southern California. [1] Ministry of Unification, “Number of North Korean Defectors Entering South Korea,” accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/whatwedo/support/. [2] Cho Eun-ah, “韓여성 키 162㎝… 100년새 20㎝ ‘폭풍 성장’ 세계 1위” [South Korean Women are 162cm on Average – 20cm Growth over the Past 100 Years], Dong-A Ilbo, July 27, 2016. https://www.donga.com/news/Society/article/all/20160727/79419892/1. [3] Fyodor Tertitskiy, “Let them eat rice: North Korea’s public distribution system,” NK News, October 29, 2015. https://www.nknews.org/2015/10/let-them-eat-rice-north-koreas-public-distribution-system/. [4] Ministry of Unification, “Policy on North Korean Defectors,” accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/relations/statistics/defectors/. [5] Lives for Sale: Personal Accounts of Women Fleeing North Korea to China (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2009), 33. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Lives_for_Sale.pdf. [6] Ahn So-young, “국제법률단체 ‘탈북 여성들 중국 동북3성에서 성착취…국제사회 대응 시급’” [The Sexual Exploitation of North Korean Women in Northeastern China Requires Urgent International Attention, says NGO], VOA Korea, March 27, 2023. https://www.voakorea.com/a/7024247.html. |

DedicationHRNK staff members and interns wish to dedicate this program to our colleagues Katty Chi and Miran Song. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed