|

By Jong-Min Lee

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations & Research On May 19, 2023, the South Korean military discovered the body of a deceased North Korean escapee in its waters. According to the South Korean authorities, roughly 70g of methamphetamine was found on the individual’s leg.[1] Considering North Korea’s past actions and their impact on nearby countries, the concerns pertaining to methamphetamine from North Korea are nothing new for South Korea. This piece examines the past and present of narcotrafficking in relation to North Korea, with a focus on China's northeastern provinces that have been most affected by this issue. History of North Korea’s State-led Narcotrafficking According to testimonies by high-ranking defectors, including Thae Yong-ho (former deputy ambassador to the UK) and Hwang Jang-yeop (former Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Supreme People’s Assembly), the North Korean regime started its narcotic-trafficking operations under Kim Jong-il’s guidance between the late 1960s and the early 1970s. This state-sponsored narcotrafficking started as an effort to prove Kim Jong-il’s political competency to his father, Kim Il-sung, by obtaining much-needed foreign currency for the regime.[2] However, this state-sponsored narcotrafficking experienced drawbacks during the 1970s. These operations caused significant diplomatic problems. Numerous North Korean diplomats were implicated for their involvement. In 1976 alone, North Korean diplomats were expelled and designated persona non grata from Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for trafficking hashish.[3] Subsequently, North Korea started to work with criminal organizations in the 1980s to mitigate diplomatic complications.[4] Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, North Korea faced significant economic difficulties and experienced a famine in the mid- to late-1990s. The North Korean regime called the famine the “Arduous March.” Professor Sandra Fahy states that “Marching through Suffering” is a more faithful translation. It connotes valiantly struggling through the dire conditions of the famine, which North Korea blamed on the United States. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse and the end of Soviet subsidies, Kim Il-sung expanded the regime’s narcotrafficking operations. In 1992, under Kim Il-sung’s orders, the cultivation of heroin was promoted on a national scale under the name of “White Bellflower Movement,” along with the production of methamphetamine, to secure foreign currency.[5] During the famine, Kim Jong-il further encouraged North Korea’s illicit operations to overcome economic challenges.[6] In 1996, there was a major shift in North Korea’s narcotics production. Severe floods and the famine damaged its poppy fields and created difficulties for heroin production. The regime thus turned to methamphetamine as an alternative.[7] Under orders from Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, North Korea’s diplomatic service, security apparatus, and numerous state agencies became involved in illicit activities.[8] For example, according to Hwang Jang-Yeop, North Korean naval vessels were routinely involved in narcotrafficking to Southeast Asia until the mid-1990s.[9] Hwang also testified in 1997 that Nanam Pharmaceutical plant managed heroin, Suncheon Pharmaceutical plant managed morphine, and Pyongyang Pharmaceutical plant managed meth production, showing deep and widespread state involvement in drug production.[10] In the case of heroin, it has been alleged that the forced labor of political prisoners was used to cultivate poppies. Satellite images have shown large poppy plantations near the Yodok political prison camp, and testimonies from refugees attest to the use of forced labor in heroin production.[11] The North Korean regime was also deeply involved in the production of crystal meth. The use of government-sanctioned pharmaceutical plants guarantees a high level of purity for the end products.[12] It has been alleged that the regime enhanced its narco-products by recruiting professional methamphetamine producers from South Korea in the early 1990s.[13] Chinese court dockets indicate that both South Korean[14] and Chinese transnational criminal organizations (TCOs)[15] have been involved in North Korea-related narcotrafficking. Extensive state involvement in narco-production and trafficking has increased the commercial value of North Korean products in the global narco-market.[16] These narcotics have been sold through North Korea’s diplomatic outposts and restaurants,[17] and also with the cooperation of various TCOs, including the Yakuza, the Russian Mafia, and the Triads.[18] It has been alleged that North Korea partnered with these organizations to cover its tracks.[19][20] Over time, this state-sponsored narcotrafficking project has resulted in the proliferation of professional narco-producers across the country. The regime has lost control over narcotics production, as these individuals are no longer constrained by the state. Drug-related crimes in North Korea have grown rampant despite the enactment of legislation on narco-control in 2004[21] and 2013.[22] Recent testimonies from refugees attest to an upsurge in public executions and criminal punishment for narcotics-related offenses.[23] North Korean meth products have also been found in the Philippines,[24] Australia,[25] China,[26] and South Korea.[27] They even came close to entering the United States in 2013.[28] China has been a major point of transit for North Korean narcotics.[29] The scale of North Korea’s narco-production and trafficking cannot be verified, mainly due to China’s unwillingness to release detailed information that could be politically sensitive.[30] In the absence of official documentation, the main source of information on the subject has been the testimonies of North Korean refugees.[31] Impact of North Korean Narcotics on the People’s Republic of China It has been widely acknowledged that North Korea’s narcotrafficking has most heavily impacted Chinese cities near the Sino-North Korean border. Although aggregated data on North Korean narcotics is unavailable, its existence and impact can be inferred from Chinese and South Korean sources. North Korean crystal meth was sold for roughly 1,200 RMB per gram in northeast China in 2010,[32] and the estimated annual North Korean production of crystal meth and other synthetic drugs is around 3,000 kg.[33] Meanwhile, South Korean sources estimate that Bureau 39, which is tasked with raising foreign currency for the North Korean regime, has been making roughly $100-200 million annually through narcotrafficking operations.[34] The high purity of North Korea’s crystal meth has made it increasingly competitive in the Chinese drug market. Police officers in northeast China have stated that North Korean crystal meth has been sold at a higher price than that from southern China, where illicit substances are obtained from the “Golden Triangle” (Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar). In contrast to crystal meth from southern China, which was sold at approximately 1g/1200 RMB (equivalent to $186), the starting price of North Korean crystal meth was approximately 1g/1500 RMB (equivalent to $232).[35] Even though exact information is not publicly available, narcotrafficking operations are likely to have been a major source of revenue for the North Korean regime. Based on Chinese court cases, relevant statistics, and statements from senior Chinese Ministry of Public Safety (MPS) officials, North Korea’s narcotrafficking operations caused significant security challenges for the Chinese government and resulted in corruption among border security personnel. In 2011, Liu Yuejin, Vice Commissioner of the National Narcotics Control Commission, commented: The number of people using methamphetamine in Northeast China has increased significantly. The abuse situation in Northeast China is prominent, and the registered synthetic drug abusers in the three Northeastern provinces have accounted for more than 72% of all drug users. To the surprise of the Chinese people, the three Eastern provinces, which are neither coastal nor drug-producing, have become the hardest hit areas. Russia and South Korea, which border the three Eastern provinces, are importers of drugs, are not important sources of exports, and only North Korea has grown to be the manufacturer of drugs on a large scale since the 1990s. There is also plenty of evidence that drugs from North Korea, especially methamphetamine, are rampant in the three Northeastern provinces.[36] Northeast China has been hit the hardest by drug problems relative to other regions of the country. According to statistics from the Yanji municipal government in 2009, the number of narcotic offenders related to crystal meth in the city in 1995 was only 44, but the number had increased to 2,090 over a decade.[37] Meanwhile, the Shenyang City Prosecution Service stated that 73% of all narcotraffickers prosecuted between 2009 and 2011 were foreign nationals.[38] These “foreign” nationals are allegedly North Koreans. Furthermore, from January to May 2015, the Jilin provincial government seized and incinerated roughly 170 kg of narcotics.[39] When the Regional Deputy Director of Ministry of Public Safety and the Commander of the Byeonbang (Border Area) Reconnaissance Battalion in Donggang City were indicted in 2015 for colluding with North Koreans, Chinese authorities seized approximately 50 kg of North Korean crystal meth during the arrest.[40] The opaqueness of narcotrafficking from North Korea also presents a significant challenge to Chinese President Xi Jinping, who declared a war on drugs in 2014.[41] In 2020, Xi re-emphasized the importance of China’s counter-narcotic efforts.[42] China’s 2019 National Drugs Situation Report identified 0.16% of its population (2.148 million) as drug users.[43] This poses a significant challenge for Xi, and China has taken steps to address the problem over the past decade. Despite the severity of this issue, information about North Korea’s narcotrafficking in China has not been publicized through foreign media outlets since 2018,[44] when there was a thaw in Sino-North Korean relations with multiple summit meetings between Xi and Kim.[45] Since then, Sino-North Korean relations have been reinforced as Sino-U.S. relations have deteriorated. Reports from the Liaoning Daily and statistics from the Intermediate People’s Court of Shenyang in 2020 note that the number of narcotics-related offenses had declined by 61.11% since 2016.[46] However, considering that North Korea enforced strong border control measures in response to COVID-19,[47][48] this decline may reflect North Korea’s extreme quarantine measures rather than a fundamental shift in policy. North Korean narcotrafficking can also be examined through information from South Korean sources. In 2012, Representative Yoon Sang-hyun of the National Assembly stated that more than half of the narcotics entering South Korea originated from North Korea.[49] The problem has only grown in recent years. The number of maritime narcotrafficking interdictions by South Korea’s Coast Guard increased from 56 in 2016 to 962 in 2022.[50] According to figures from the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office, the amount of confiscated heroin increased from 0.74g in the first half of 2020 to 1,210.26g in the first half of 2021, while the amount of seized methamphetamine jumped from 28,114.19g in the first half of 2020 to 93,065g in the first half of 2021.[51] These figures do not provide specific information about narcotrafficking originating from North Korea. However, given the past frequency of indictments and announcements by South Korean authorities implicating North Korea in narcotrafficking incidents, it is plausible that North Korea is involved in these developments. North Korea’s Narcotrafficking: Recent Developments Kim Jong-un has demonstrated a willingness to cooperate with China on drug-related issues. In particular, the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) passed a new counter-narcotics law in July 2021. Compared to the 2004 and 2013 amendments that only included clauses related to the punishment of the production and trafficking of narcotics, this new law has a special provision that specifically refers to the prevention of narcotics usage and related crimes.[52] Considering the statements and relevant data from Chinese officials in the three northeastern provinces and from North Korean refugees, however, the new law is unlikely to have a meaningful impact. The severity of narcotics usage among North Koreans may be attributed to state-sponsored narcotics production and distribution, a dilapidated healthcare system, food insecurity, and the rise in demand and distribution of narcotics throughout North Korea and its vicinity. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the famine in the 1990s devastated North Korea’s economy, public distribution system, and public health infrastructure. More North Koreans turned to illicit substances to evade hunger, illness, and pain.[53] The severity of the issue is indicated by the testimony of a former North Korean counternarcotics prosecutor, who stated in a 2021 article that roughly 30 percent of the North Korean population has abused illicit substances. The problem is not solely restricted to adults. This former prosecutor testified that she had even witnessed seven-year-olds abusing narcotics.[54] A study by the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights in 2018 reached similar conclusions regarding the percentage of the population affected by drug abuse.[55] The gravity of the problem has also been well described in testimony from Chinese law enforcement. Yanbian police officers stated in a 2014 study that most North Korean households stored at least 2 grams of narcotics as first-aid medicine.[56] To stabilize the region and to counter the spread of narcotics in northeast China, Chinese authorities initiated a cooperative investigation with South Korean authorities in 2011.[57] South Korea and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in Enforcement of Criminal Laws for transnational crimes. However, compared to China's existing transnational counter-narcotic measures with ASEAN countries—ASEAN and China Cooperative Operations in Response to Dangerous Drugs (ACCORD)—Sino-South Korean cooperation on transnational crimes is not as well structured. Chinese authorities have often demonstrated a lack of cooperation in terms of the South Korean authorities’ requests for extradition and investigations of transnational crimes.[58] Furthermore, it has been alleged that Chinese authorities have been hesitant to actively apprehend North Korean operators based on shifting bilateral relations and the geopolitical climate.[59] Concluding Remarks North Korea’s narcotrafficking not only affects China, but also impacts South Korea, which has been experiencing an increase in methamphetamine-related cases. South Korean police and prosecutors have frequently referred to narcotrafficking cases involving narcotics originating from North Korea, with references to North Korea’s Ministry of State Security.[60] On October 26, 2022, South Korea’s President Yoon and the ruling People Power Party (PPP) declared a war on drugs.[61] Earlier this year, there were revelations about a methamphetamine blackmail scheme targeting minors at a cram-school in Seoul, with the methamphetamine originating from China.[62] South Korea has been experiencing an increase in methamphetamine-related narcotrafficking cases, some of which may plausibly involve North Korea and other TCOs. While cooperation between China and South Korea is needed to effectively address this issue, it is unclear whether such cooperation will be forthcoming. Consider, for example, the lack of cooperation thus far between the United States and China regarding the fentanyl crisis.[63] The current geopolitical environment does not appear to be conducive to significant bilateral cooperation between Seoul and Beijing on narcotrafficking, including narcotics originating from North Korea. Jong-Min Lee is a Master of Arts in Law & Diplomacy candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, pursuing a concentration in International Security and Public International Law. He is a graduate of the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University, where he pursued a concentration in Security Policy and Global Public Health. [1] Kim Yejin, “마약 들고 탈북 추정...북한 남성 시신 발견해 조사 중” [Suspected to have escaped from North Korea with Narcotics... Authorities are Investigating after the Body of a Deceased North Korean Man is Found], Segye Ilbo, May 27, 2023. https://m.segye.com/view/20230527505240. [2] Thae Yong-ho, “북한에 마약 많이 퍼졌다는 소문 돌지만... 실제론 철저히 단속” [Despite the Rumors of Prevalence of Narcotics in North Korea, the Authorities have Responded with Strict Measures], Chosun Ilbo, April 27, 2023. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/04/26/2019042602028.html. [3] “Letter from Norwegian Police Security Service to Foreign Ministry, “The North Korean Embassy-Illegal Import and Distribution of Spirits, Cigarettes, etc.,” The Wilson Center Digital Archive, March 28, 2017. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/letter-norwegian-police-security-service-foreign-ministry-north-korean-embassy-illegal?_ga=2.196974126.321082836.1627586055-1512673604.1622236090&_gac=1.219723243.1626069560.Cj0KCQjwraqHBhDsARIsAKuGZeGaI3t0CVh5E0--v3SlEoOhNqLnVITICdtPvYlXg9PqOfLDsdfu8zsaAuF6EALw_wcB. [4] William Bach, “Drugs, Counterfeiting, and Arms Trade: The North Korean Connection,” 2001-2009 Archive for the U.S. Department of State, May 20, 2003. https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/inl/rls/rm/21044.htm. [5] Hwang Hyung-joon, “양귀비 직접 재배해 마약 제조’…북한군의 ‘백도라지 사업’” [Producing Narcotics through Cultivating own Poppy Plantations…Korean People’s Army’s “White Bellflower Project”], Dong-A Ilbo, December 8, 2008. https://www.donga.com/news/Politics/article/all/20081208/8668334/1. [6] Jang Won-jae, “장원재의 북한 요지경: ‘마약의 나라’ 북한 주민의 30%가 마약 상복” [Country of Narcotics: 30% of North Korean Population Abuses Narcotics], Monthly Chosun, November 2019. http://monthly.chosun.com/client/news/viw.asp?ctcd=&nNewsNumb=201911100048. [7] Lee Hong, “추적! 평양發 마약 커넥션의 내막 국가기관이 헤로인ㆍ필로폰 밀조ㆍ밀매를 주관하는 세계 유일의 사례 연구” [Drug Ring Originating from Pyongyang, Research on the World’s Only Narco-State, the Drug Rings’ Connection to North Korea’s State-led Production and Smuggling of Heroin and Methamphetamine], Monthly Chosun, July 2003. http://monthly.chosun.com/client/news/viw.asp?ctcd=&nNewsNumb=200307100056. [8] Michael Miklaucic and Moisés Naím, “The Criminal State,” in Convergence: Illicit Networks and National Security in the Age of Globalization, eds. Michael Miklaucic and Jacqueline Brewer (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 2013), 164–65. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/convergence.pdf. [9] Yang Jung-ah, “황장엽 ‘김정일 비자금 마카오-광저우 두 곳에서 관리” [Hwang Jang-yeop says Kim Jong-il’s Slush Funds are managed in Macau and Guangzhou], Daily NK, January 16, 2006. https://www.dailynk.com/%ED%99%A9%EC%9E%A5%EC%97%BD-%EA%B9%80%EC%A0%95%EC%9D%BC-%EB%B9%84%EC%9E%90%EA%B8%88-%EB%A7%88%EC%B9%B4%EC%98%A4%EA%B4%91%EC%A0%80%EC%9A%B0/. [10] Jang, “Country of Narcotics.” [11] Ed Barnes, “Flourishing Poppy Fields Outside Prison Camps Are Heroin Cash Crop for North Korea,” Fox News, May 10, 2011. https://www.foxnews.com/world/flourishing-poppy-fields-outside-prison-camps-are-heroin-cash-crop-for-north-korea. [12] Jang, “Country of Narcotics." [13] Jung Hee-sang, “한국 기술자 2명, 북한에서 마약 제조” [Two South Koreans are Producing Narcotics in North Korea], Sisa Journal, November 11, 2001. https://www.sisajournal.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=79131. [14] Liu Yang, “两名韩国人在中国东北地区贩毒 分获死刑及死缓” [Two South Koreans Sentenced to Death for Narcotrafficking in Northeast China], Sohu, August 14, 2012. http://news.sohu.com/20120814/n350626755.shtml. [15] Liu Li, “家禁毒委、公安部公布近期破获的十起毒品大案” [The National Narcotic Control Commission and the Ministry of Public Safety’s Ten Major Counter-Narcotics Sting Operations], China Central Television, June 25, 2008. http://news.cctv.com/society/20080625/106509.shtml. [16] Jung, “Two South Koreans are Producing Narcotics in North Korea.” [17] Joo Seong-ha, “마약에 빠진 북한… ‘동네마다 얼음 파는 집’” [North Korea on Drugs… ‘Prevalence of Methamphetamine’], Dong-A Ilbo, May 25, 2019. https://www.donga.com/news/Politics/article/all/20190525/95690028/1. [18] Bach, “Drugs, Counterfeiting, and Arms Trade.” [19] David L. Asher, “Policy Forum 05-92A: The North Korean Criminal State, its Ties to Organized Crime, and the Possibility of WMD Proliferation.”, Nautilus Institute, November 15, 2005. https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/the-north-korean-criminal-state-its-ties-to-organized-crime-and-the-possibility-of-wmd-proliferation/?msclkid=808ba4d8b6db11ecbe8709e0f0316cb3. [20] Miklaucic and Naím, “The Criminal State,” 164–65. [21] Yang Ok-kyung et al., “Bukhan jumin-ui mayak sayong mit jungdok” [North Korea’s Illegal Drug Use and Abuse: Current Situation and Solutions], Dong-A Yeongu 37, no. 1 (2018): 233–70. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002323057. [22] Ibid. [23] Oh Gyeong-seob et al., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2021 (Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute for National Unification, 2021), 45–56. https://www.kinu.or.kr/main/module/report/view.do?idx=837&nav_code=mai1674786121. [24] Rosette Adel, “Sebastian: Drugs in Bilibid come from China, North Korea,” Philstar Global, October 10, 2016. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2016/10/10/1632237/sebastian-drugs-bilibid-come-china-north-korea. [25] Doug Struck, “Heroin Trail Leads to North Korea,” The Washington Post, May 12, 2003. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2003/05/12/heroin-trail-leads-to-north-korea/017fa657-ce96-4eae-b44e-16f9376816ff/. [26] Son Hye-min, “북 보위성 소속 마약밀수조직 중국 공안에 체포돼” [Drug Ring under North Korea’s Ministry of State Security Operatives have been Apprehended by the Chinese Ministry of Public Safety], Radio Free Asia, May 24, 2019. https://www.rfa.org/korean/in_focus/ne-hm-05242019090806.html. [27] Ibid. [28] Sari Horwitz, “5 Extradited in Plot to Import North Korean Meth to U.S.,” The Washington Post, November 20, 2013. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/5-extradited-in-plot-to-import-north-korean-meth-to-us/2013/11/20/4a2a3840-5222-11e3-9e2c-e1d01116fd98_story.html. [29] “중국 지린성, 북-중 마약밀매 거점부상” [Jilin Province of China has become the epicenter of Sino-North Korean Narcotrafficking], VOA News, January 26, 2010. https://www.voakorea.com/a/a-35-2010-01-26-voa22-91428629/1331770.html. [30] Wang Jiawei et al., “朝鲜攻陷东北” [North Korea Narcotics Took Over Northeast China], Wenmi, October 24, 2022. https://www.wenmi.com/article/pzv4j903t2ri.html. [31] U.S. Department of State, 2017 INCSR-Volume I: Drug and Chemical Control (as Submitted to Congress), March 2, 2017, 143. https://www.state.gov/2017-incsr-volume-i-drug-and-chemical-control-as-submitted-to-congress/. [32] Choi Won-gi, “북한 사회의 마약 실태” [The Drug Problem in North Korea], VOA Korea, August 11, 2010. https://www.voakorea.com/a/nk-drug-100462074/1347301.html. [33] Lee Dong-hwi, “북한産 필로폰 국내 유통시킨 19명 검거” [Nineteen Individuals Arrested for Distributing North Korean Meth], Chosun Ilbo, October 10, 2019. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/10/08/2019100800156.html. [34] Lee Jang-hoon, “북한 노동당 39호실의 외화벌이 사업” [Korean Workers’ Party Bureau 39’s Foreign Currency Operations], Monthly Chosun, August 2015. http://monthly.chosun.com/client/news/viw.asp?ctcd=&nNewsNumb=201508100036. [35] Sheena Chestnut Greitens, Illicit: North Korea’s Evolving Operations to Earn Hard Currency (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2014), 85–88. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/SCG-FINAL-FINAL.pdf. [36] Li Cong, “Drugged by Comrades,” Global Times, March 12, 2013. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/201303/767651.shtml. [37] Kim Kyong-chan et al., “Joongguk dongbuk jiyeok hanguk gwallyeon mayak beomjoe wa boisu pishing beomjoe ui siltae mit daeung bangan-e gwanhan yeongu” [The Research and Legal Studies on the Policy and the Trends of Drug and Voice Phishing Crime Related to Koreans in Northeast China] (Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute of Criminology, 2014), 100. https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE02393421. [38] Ibid., 63. [39] “길림성 마약 170여키로그람 집중소각” [Jilin Province Incinerates 170kg Worth of Narcotics], People’s Network, June 24, 2015. http://korean.people.com.cn/85524/15516533.html. [40] Joo, “North Korea on Drugs.” [41] Shannon Tiezzi, “China's War on Drugs,” The Diplomat, May 29, 2015. https://thediplomat.com/2014/08/chinas-war-on-drugs/. [42] “习近平对禁毒工作作出重要指示强调 坚持厉行禁毒方针 打好禁毒人民战争 推动禁毒工作不断取得新成效” [President Xi Jinping Issues Important Instructions and Expects Effective Results on Counter-Narcotic Efforts and Declares People’s War on Drugs], Xinhua, June 23, 2020. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-06/23/c_1126150124.htm. [43] Aksu District Public Security Bureau Cyber Division, 《2019年中国毒品形势报告》发布(附全文) [China’s National Drug Situation Report 2019 (Full Text)], Baidu, June 25, 2020. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1670462119974013484&wfr=spider&for=pc. [44] Author’s finding from researching major Chinese internet portals and state media outlets. [45] Steven Lee Myers and Jane Perlez, “Kim Jong-Un Met with Xi Jinping in Secret Beijing Visit,” The New York Times, March 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/27/world/asia/kim-jong-un-china-north-korea.html. [46] Zhou Xianzhong et al., “市法院发布禁毒工作白皮书(2016-2020)” [City Court Releases White Paper on Anti-drug Work (2016-2020)], Shenyang Net, June 23, 2021. https://news.syd.com.cn/system/2021/06/23/011925533.shtml. [47] Jesse Jonson, “North Korea Closes Borders to All Foreign Tourists as New Coronavirus Spreads from China,” The Japan Times, January 22, 2020. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/01/22/asia-pacific/science-health-asia-pacific/north-korea-closes-borders-all-foreign-tourists-coronavirus-china/. [48] Ji Jeong-eun, “North Korea Accepts Pandemic Aid, but Border with China Remains Closed,” Radio Free Asia, October 7, 2021. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/aid-10072021191235.html. [49] Jung Ah-ran, “윤상현 ‘국내반입 마약 절반 이상이 북한산’” [Rep. Yoon Sang-hyun: ‘More than half of the Narcotics in South Korea originates from North Korea’], Yonhap News, February 6, 2012. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20120206062000001. [50] Republic of Korea Coast Guard, “지표서비스 나라 지표-마약사범 단속 현황” [Statistics on Apprehension and Crackdown of Narcotraffickers], January 9, 2023. https://www.index.go.kr/unity/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do;jsessionid=9HQEWIWkUeP6_phzbGwjMQS57_jVe8jh8hoZrYhQ.node11?idx_cd=A0001. [51] Supreme Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Korea, “2021년 6월 마약류 월간동향” [2021 June Report: Monthly Trends for Narcotrafficking], July 23, 2023. https://www.spo.go.kr/site/spo/ex/board/List.do?cbIdx=1201. [52] Lee Myong-cheol, “북, 마약사범 급증에 ‘마약범죄방지법’ 새로 제정” [North Korea Newly Adopts ‘Drug Crime Prevention Act’ to Counter Increase of Narcotic-Related Offenders], Radio Free Asia, August 3, 2021. https://www.rfa.org/korean/in_focus/ne-lm-08032021091443.html. [53] Yang et al., “North Korea’s Illegal Drug Use and Abuse.” [54] Ahn Yong-hyun, “주민 30% 마약...한류에 푹빠져’ 김정은이 말한 '악성암' 北 덮쳤다” [30% of the Population Suspected to Abuse Narcotics, Absorbed in Korean Wave; ‘Terminal Cancer’ Mentioned by Kim Jong-un has Struck North Korea], Chosun Ilbo, July 23, 2021. https://www.chosun.com/politics/north_korea/2021/07/23/ER57Y5DENZGILNAAW7V2KLDAUM/. [55] Koo Eun-hyung, “이관형 “북한은 왜? <北 주민 30%... 마약 경험?>” [Why has 30% of North Koreans Experienced Narcotics?], MBC News, December 19, 2016. https://imnews.imbc.com/replay/unity/4186812_29114.html. [56] Kim et al., “The Research and Legal Studies on the Policy and the Trends of Drug and Voice Phishing Crime Related to Koreans in Northeast China,” 97. [57] Yoon Wan-jun, “[단독]中, 북한산 마약에 뿔났다” [Exclusive: China Infuriated over North Korean Narcotics], Dong-A Ilbo, July 5, 2011. https://www.donga.com/news/Inter/article/all/20110705/38547901/1. [58] Song Young-ji, “Han joong hyeongsa sabeop gongjo-eui munjaejeom-gwa gaesun bangan” [Problems in International Mutual Assistance between Korea and China and the Improvement Plan], Kangwon Law Review 59 (2020): 263–94. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002567640. [59] Son Hye-min, “China Uncovers North Korean State-Sponsored Drug Ring after Arrests,” Radio Free Asia, October 11, 2020. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/nk-china-meth-agents-05282019164756.html. [60] For example, see Park Hyun-jun, “검찰, 北에 포섭돼 마약판매 시도 50대 구속기소” [Prosecution Service Indicts 50-year-old for Attempting to Sell Narcotics on North Korea’s Behalf], Asia Business Daily, May 25, 2010. http://cm.asiae.co.kr/article/2010052516351574974. [61] Lee Sung-eun, “Yoon, PPP Declare War on Drugs,” Korea JoongAng Daily, October 26, 2022. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2022/10/26/national/socialAffairs/korea-drugs-drug-smuggling/20221026184624813.html. [62] Jun Ji-hye, “Police Request Chinese Authorities’ Assistance in Drug-Laced Drinks Case,” The Korea Times, April 10, 2023. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/05/113_348773.html. [63] Vanda Felbab-Brown, “China’s Role in the Fentanyl Crisis,” The Brookings Institute, March 31, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-role-in-the-fentanyl-crisis/.

0 Comments

By Diletta De Luca, HRNK Research Associate

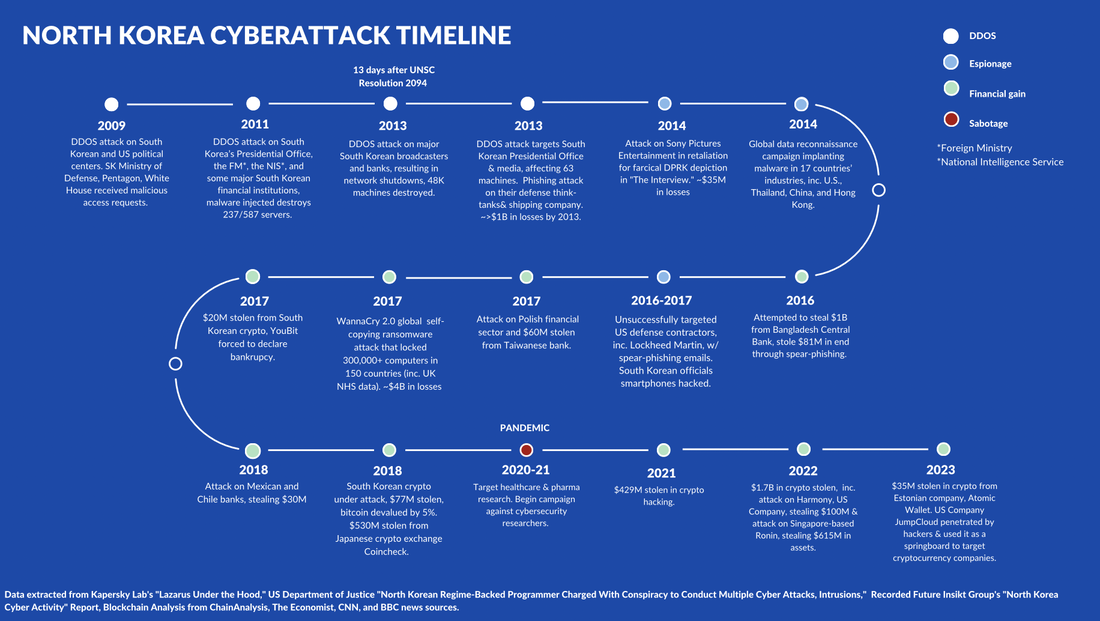

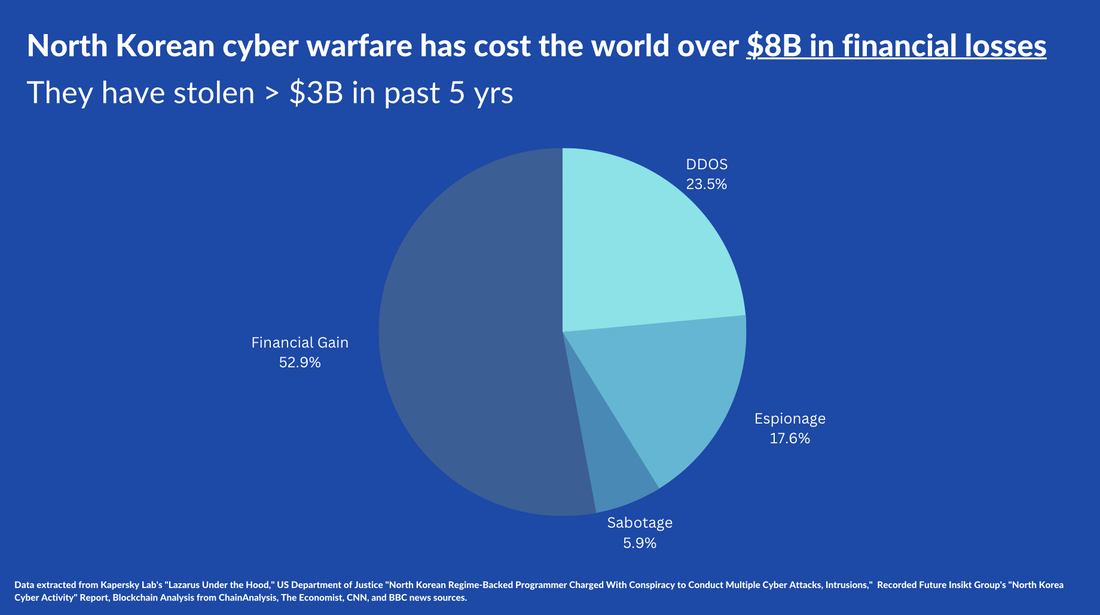

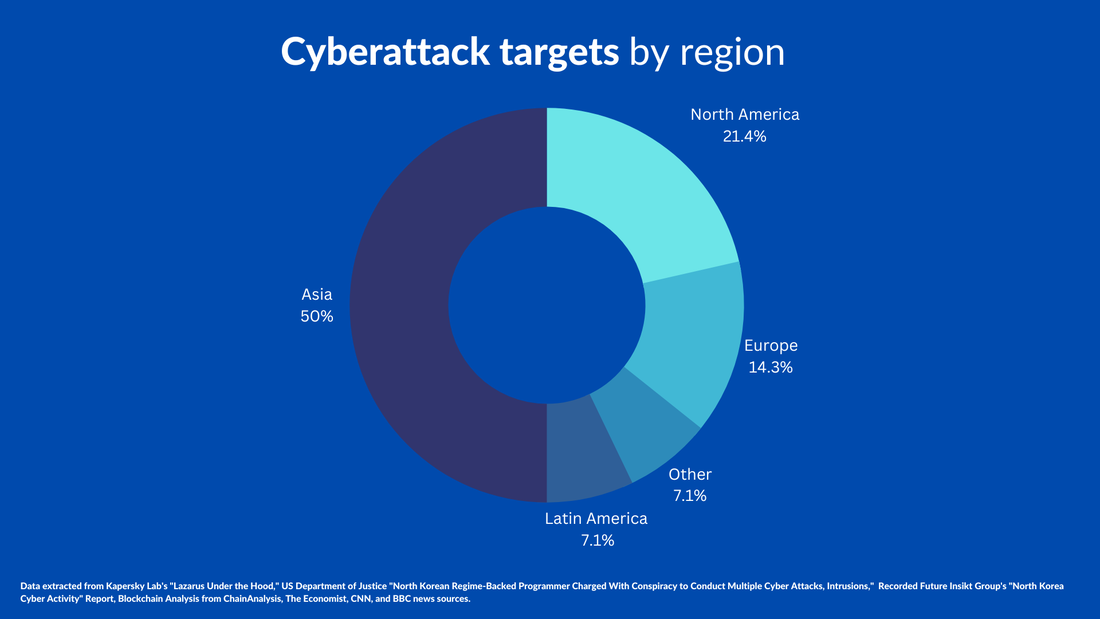

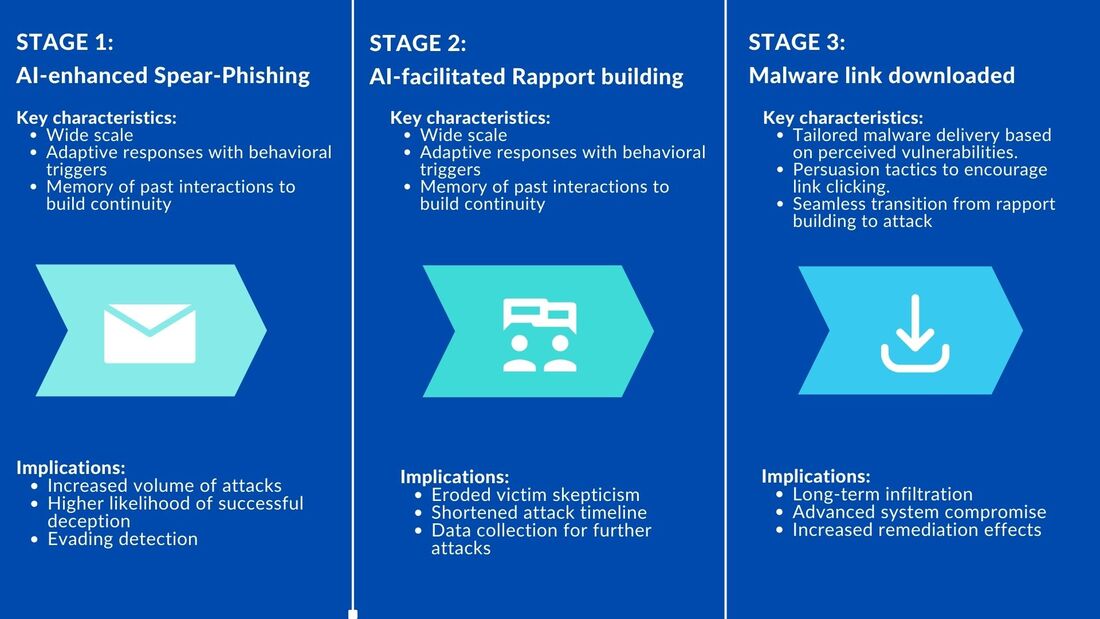

Edited by Cherise Kim (former HRNK Research Intern) and Raymond Ha (HRNK Director of Operations & Research) In 2014, the United Nations (UN) Commission of Inquiry on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) concluded that the North Korean regime was perpetrating crimes against humanity.[1] Among the human rights concerns noted by the COI, the North Korean regime has been accused of systematically violating the Right to Food of its citizens. Food insecurity in the country is not a recent development. The most devastating food emergency the country experienced dates back to 1995, when the regime officially acknowledged the so-called “Arduous March.”[2] Yet, the people of North Korea continue to remain food insecure today. Food Insecurity in North Korea Today In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights first enshrined the right to adequate food in Article 25.[3] Subsequently, the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) further defined the Right to Food as “the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger.”[4] As a party to the ICESCR since 1981, North Korea is among the 171 countries[5] that are obligated to respect this right.[6] Nevertheless, the North Korean population continues to suffer from high levels of malnutrition and food insecurity. The UN’s 2022 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report classifies North Korea as one of the countries with the largest number of malnourished people in the world—41.6 percent of the population is undernourished.[7] Despite ongoing international concern and efforts to mitigate chronic food insufficiency in the country, the most catastrophic food emergency recorded in North Korea dates to the second half of the 1990s. This famine, often referred to as the Arduous March, is estimated to have killed up to 1 million North Koreans—approximately 5 percent of the population.[8] The 1995 Famine Scholars and analysts believe that North Korea’s food crisis began to unfold in the 1980s, before the regime publicly acknowledged the emergency.[9] The causes of the famine were formally attributed to a severe economic crisis and natural disasters. During the early 1990s, North Korea experienced economic difficulties following the collapse of the Soviet Union and internal reforms unfolding in China.[10] Its two major trading partners, which had supported the country through favorable pricing and other economic assistance, suddenly cut their exports, provoking economic instability in North Korea.[11] With almost no exports and minimal diplomatic and economic relations with countries outside the Soviet sphere of influence, the country had to rely on domestic agricultural production. Natural disasters in 1995, including floods and droughts, further reduced the country’s agricultural production and ability to provide food its own citizens.[12] As the crisis continued to worsen, the North Korean regime did not take any action to improve the situation. By the end of 1995, international assistance was provided by the World Food Programme, non-governmental organizations, and individual countries through bilateral aid, mainly from South Korea.[13] Although the famine eventually passed, food insecurity has remained a chronic problem ever since. North Korea’s Obligations on the Right to Food In 1999, the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights issued General Comment 12 on the Right to Food. The comment outlines three obligations for states in ensuring the right to adequate food: the obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill.[14] The North Korean regime neglected all three during the famine of the 1990s. The obligation to respect is a negative responsibility that prevents states from adopting measures that could ultimately preclude access to adequate food for all or part of their populations. In the 1990s, the poorest North Korean citizens engaged in market activities to access food. Many sold foodstuffs in local markets, but some also turned to prostitution, theft, or defection.[15] The regime prevented citizens from engaging in such market activities, as these were considered capitalist and therefore disloyal to the regime.[16] The consequences ranged from punishment to imprisonment and even execution. Moreover, after receiving aid from humanitarian agencies, major constraints were imposed on foreign workers. This prevented foreign aid agencies from assisting the most vulnerable segments of the population, as they could not access specific geographical areas. Information flows within the country were restricted, and it was not possible to properly monitor the distribution of aid. Consequently, most humanitarian organizations withdrew from the country only after a few years.[17] As the regime perceived humanitarian operations as a political threat, the strict restrictions imposed made it impossible for foreign workers to assess the needs of people in remote areas and evaluate the impact of their efforts.[18] The Kim regime ultimately precluded and obstructed the provision of assistance to segments of its population, which constituted a breach of its obligation to respect. The obligation to protect is the requirement for states to adopt measures that ensure that no individual is deprived of their Right to Food. This was violated by the North Korean regime in multiple ways. First, the regime lacked the political will to effectively assist its population. Scholars characterized the famine as a “priority regime famine,” meaning that the regime prioritized ideological programs over feeding citizens for strengthening its authority.[19] The famine was therefore the result of the regime’s deliberate decision to prioritize its own political and ideological agenda over the welfare of its people, resulting in mass starvation. It could have increased access to food by reallocating resources assigned to the military and the elite, but it decided otherwise.[20] Second, issues of distribution and entitlement caused the poorest and most vulnerable individuals to suffer the worst consequences. Access to food was and still is determined by one’s songbun, a socio-political classification assigned at birth that is based on one’s family background. It is a means through which the regime determines and controls all aspects of citizens’ lives based on their perceived loyalty to the Kim family. Based on this classification, citizens are assigned to one of three classes—the “core (loyal) class, the “wavering” class, or the “hostile” class. One’s songbun determines decisions about residency, occupation, access to food, health care, education, and other services. In turn, the songbun system allows the regime to maintain and reinforce its political control over the population.[21],[22] Based on one’s songbun, entitlements to food are strictly defined. Access to food has continued to be seriously limited for those who are not considered loyal to the Kim family, decreasing their chances of survival. During the Arduous March, the areas closer to Pyongyang, where most of the elite is located, received significant food assistance while more remote areas of the country remained inaccessible to humanitarian workers.[23] The famine and the failure of the regime to protect its citizens were clear manifestations of widespread violations of human rights, perpetrated by the regime to strengthen its power and reinforce its ideology. Finally, the obligation to fulfill, which includes the facilitation and promotion of conditions and resources that allow citizens to enjoy their Right to Food, was also neglected. As mentioned above, resources were not equitably distributed among the population. Privileged groups such as the military, the elite, and members of the Korean Workers’ Party never faced food insecurity as they continued to receive food rations and foodstuff. The rest of the population had no possibility to call upon the regime to provide assistance and respect their basic human rights.[24] Nevertheless, the regime could have increased access to food by allocating less resources to the military and the security apparatus.[25] The famine was the result of the Kim regime’s deliberate decision to prioritize its own power and stability over the rights and welfare of its citizens. Concluding Remarks Today, the situation remains precarious. News coverage of the ongoing food crisis in North Korea is recurrent, as the circumstances have been further aggravated by the closure of the country’s borders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the war in Ukraine has worsened the situation due to the widespread global price increase for food, energy, gas, and fertilizers.[26] Regardless, the government’s continued investment in its security apparatus, nuclear weapons, and missiles while its population continues to starve highlights the regime’s deliberate neglect of its responsibilities and its people’s human rights. The famine of the 1990s, as well as the current food crisis that the North Korean people are enduring, constitute violations of a wide range of basic human rights other than the Right to Food. The North Korean regime’s infringements of its international obligations also include violations of socio-political rights and physical integrity.[27] It therefore remains essential for the international community to continue to urge the North Korean regime to respect its obligations and ensure the fundamental human rights of its population. Diletta De Luca has a Master of Science (cum laude) in Political Science from the University of Amsterdam and is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in International Security Studies at the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies & the School of International Studies at the University of Trento. [1] United Nations Human Rights Council, “Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” A/HRC/25/CRP.1, February 14, 2014. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/108/71/PDF/G1410871.pdf?OpenElement. [2] As defined by Heonik Kwon (“Chapter 8: Time Consciousness in North Korea’s State Security Discourse” in Times of Security: Ethnographies of Fear, Protest and the Future, edited by M. Hoolbraad and M. A. Pedersen, Routledge, 2013), the term refers to “the (North Korean) political community's unwavering determination to ‘raise the flag of socialism high’ despite the collapse of the Soviet-let socialist international order, including the readiness to undergo economic difficulties and political isolation entailed by this proud negation of postsocialism” (p. 203). [3] United Nations, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” 1948. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf. [4] United Nations General Assembly, “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” Art. 11, para 2, 1966. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/cescr.pdf. [5] As of September 2023. [6] United Nations Treaty Collection, “Chapter IV: Human Rights. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” n.d. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-3&chapter=4&clang=_en. [7] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) Report - 2022, July 7, 2022. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000140990/download/?_ga=2.166537143.822104784.1671276365-431266521.1671276365. [8] Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Hunger and Human Rights: The Politics of Famine in North Korea (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2005). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Hunger_and_Human_Rights.pdf. [9] Sandra Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger,” in Dying for Rights: Putting North Korea’s Human Rights Abuses on the Record (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). [10] Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, “Chapter 1: Introduction, Famine, Aid, and Markets in North Korea” & “Chapter 2: The Origins of the Great Famine,” in Famine in North Korea: Markets, Aid, and Reform (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). [11] Daniel Goodkind and Loraine West, “The North Korean famine and its demographic impact,” Population and Development Review 27, no. 2 (2001): 219–38. [12] In July and August 1995, floods led to a decrease in the grain production of almost 2 million tons. In 1997, droughts affected the breadbasket of the country (North Korea's southern provinces, many of which had been affected in previous years as well), leading to grain losses as high as 1.9 million tons. Goodkind and West (2001) provide a detailed summary of the impact of the natural disasters over different areas of the country. [13] Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger.” [14] United Nations Economic and Social Council, Committee on Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights, “General Comment 12,” E/C.12/1999/5, May 12, 1999. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838c11.pdf. [15] Haggard and Noland, “Chapter 1: Introduction, Famine, Aid, and Markets in North Korea” & “Chapter 2: The Origins of the Great Famine.” [16] Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger.” [17] Goodkind and West, “The North Korean famine and its demographic impact.” [18] Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger.” [19] Ibid. [20] Ibid. [21] Robert Collins, Marked for Life: Songbun, North Korea’s Social Classification System (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2012). https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_Songbun_Web.pdf. [22] United Nations Human Rights Council, A/HRC/25/CRP.1, February 14, 2014. [23] Ibid. [24] Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, “North Korea: Case for New International Treaty on the Right to Food,” Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law 15 (2014): 31–50. [25] Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger.” [26] Kim Tong-Hyung, “North Korea party meeting set to discuss ‘urgent’ food issue,” Associated Press, February 6, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-politics-north-korea-government-china-nuclear-weapons-30f247b53975c410e96c2246de301ad5. [27] Fahy, “Chapter 2: Famine and Hunger.” By Tiana Lakhani, HRNK Research Intern Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research At the 2016 World Economic Forum, a landmark term was coined—the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” This conceptual framework has grown to symbolize a new era, one that is characterized by rapid technological advancements and their profound implications on the global socio-economic and political landscapes. Artificial Intelligence (AI), as a cornerstone of this revolution, has been rapidly adopted globally, prompting urgent discussions about potential threats and opportunities. In the context of these discussions, one nation draws peculiar attention: North Korea, universally recognized as the most isolated and enigmatic country in the world. The question that arises is, how does North Korea, cloaked in secrecy and governed by a tightly controlled regime, engage with this global phenomenon? Is the inclusion of AI into North Korea's cyber strategies a futuristic aspiration, or could it be an emerging reality hidden in the obscurity of this enigmatic state? The prospect of AI playing a role in North Korea's cyber landscape might not be as distant as it appears. The Korean Peninsula has long been stuck in a military impasse, a situation that is decidedly unfavorable for North Korea. Faced with a desire to alter this status quo, yet constrained by the high risks associated with conventional military methods, North Korea has turned to cyber capabilities as an alternative. This strategic pivot represents an asymmetric strategy that allows North Korea to bypass the deadlock via a path of lesser resistance, defined by low-intensity, low-cost, and low-risk operations. This provides an effective way of circumventing harsh sanctions that target sources of funding for their missile and nuclear programs. Experts believe that North Korea has fostered a robust organizational structure capable of executing consequential cyber operations, as demonstrated by their alleged involvement in the Sony attack in 2014. Contrary to what one might expect from such a secluded nation, North Korea boasts a surprisingly strong technological base that reinforces its cyber capabilities. AI has the potential to augment spear-phishing campaigns by automating attacks, tailoring deceptive messages, and creating counterfeit identities, strengthening cyberattack capabilities. This technology could be attractive for North Korea to leverage, as it represents an extension of their existing cyber strategies, enabling more sophisticated and targeted approaches for financial gain. This could affect the right to privacy on a global scale. However, it is essential to recognize that the application of AI in this context is still in the early stages, with limitations in scalability and effectiveness. By investigating this intersection of technology and cybersecurity, this essay concludes that careful monitoring of advancements, encouraging international cooperation, applying further pressure on complicit nations such as China, and utilizing “naming-and-shaming” strategies are effective in combatting these emerging threats. This essay contributes to a measured understanding of the evolving landscape of cyber warfare and underline the importance of a coordinated, global response. Technological Landscape and Cyberattacks Pre-AI Integration Image A reveals a discernible shift in strategic focus in the evolution of North Korea’s cyber activities. The period between 2009 and 2013 was predominantly characterized by the deployment of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, which are disruptive attacks that paralyze computer networks. There was a strategic transition from 2014 to 2017, where North Korean cyber operations exhibited a mix of espionage and financial gain objectives. However, after 2017, there was a dramatic refocusing towards financial gain. This shift coincides with a period of severe economic contraction in North Korea, with 2020 marking the most significant shrinkage in the country’s economy in 23 years. This demonstrates a strategic pivot from the deployment of DDoS attacks towards cyber operations aimed explicitly at financial gain. This underscores maturation in North Korean cyber strategies and sheds light on the regime’s interest in these activities as a low-risk revenue stream in the coming years. The sheer financial impact of North Korea's cyber warfare activities underscores its urgency as a global concern, as revealed in Image B. Their cyber operations have cost the international community staggering sums, and the range of their operations has proven remarkable. Yet, these figures only begin to scratch the surface of their impact, failing to account for the equally significant, yet intangible, costs associated with data breaches, data theft, and the ensuing erosion of trust in digital systems. Beyond financial institutions and corporate entities, North Korea's hacking operations have breached personal devices, thereby gaining unauthorized access to private information, and have even infiltrated healthcare systems, as evidenced by an incident involving the U.K.’s National Health Service. Such transgressions not only threaten our individual privacy and security, but also have wider implications for the integrity and resilience of our increasingly digital society. Furthermore, the potential integration of AI into North Korea's cyber arsenal could significantly exacerbate these threats. AI technologies can automate and scale hacking activities, thereby augmenting their speed, sophistication, and impact. The fusion of AI with cyber warfare capabilities hence stands to dramatically inflate both the frequency and severity of cyberattacks, rendering this issue all the more pressing. In the face of such a multi-faceted threat, a comprehensive, globally coordinated response is warranted and required. An analysis of North Korea's cyberattack strategies reveals discernible patterns and priorities that vary across different geographic regions, as showcased in Image C. South Korea, for instance, absorbs the majority of North Korea’s malicious cyber activity in Asia, accounting for half of all such incidents. The character of these incursions in Europe is more differentiated. North Korea directly targets the financial sectors of less developed nations like Poland, while it seeks to exploit valuable data in more advanced countries, such as the U.K., as evidenced by the 2017 ransomware attack. The United States has experienced a notable shift in North Korean cyber aggression. Initially, North Korea's activities, starting in 2009, were primarily aimed at disrupting political systems, as revealed in Image A. However, there has been a reorientation towards financial gain in recent years, with U.S. companies becoming increasingly targeted. Furthermore, North Korea has found a profitable avenue in cryptocurrencies, amplifying their gain from cyber operations. Other developing nations like Chile and Mexico have also suffered significant financial losses, estimated at around $30 million. The potential integration of AI into North Korea's cyber capabilities is a worrisome prospect. AI could amplify the reach, scale, and sophistication of these attacks, increasing both the number of targets and the severity of damage. Given North Korea's evolving strategies and targets, the integration of AI would likely enable them to infiltrate more secure systems, automate complex attacks, and ultimately exacerbate the global threat they pose. Post-AI Weaponization: Scenario Analysis Stage 1: Spear-phishing Stage 2: Luring – “building a rapport” Stage 3: Malware link is sent and downloaded by recipient Spear-phishing serves as the “Trojan Horse” for North Korean hackers, granting them the initial access necessary to launch DDoS attacks, engage in espionage, or enact acts of sabotage for financial gain. Upon closer examination, two principal strategies emerge wherein the integration of AI could significantly enhance the efficacy of these nefarious activities: the automation of attacks and the creation of counterfeit personas. By leveraging AI's autonomous problem-solving skills, as evidenced by Large Language Models (LLMs) and the Algorithm Distillation (AD) technique, North Korean attackers could automate the process of sending deceptive emails or messages. This could involve a complex task decomposition where the AI breaks down the large task of sending spear-phishing emails into smaller, manageable subgoals, making the attack process more efficient and widespread. Furthermore, AI's ability for self-reflection and learning from past experiences could be exploited to refine and improve attack strategies based on past successes or failures, making future attacks more effective. This could also involve using AD to train the AI systems more efficiently in various phishing tactics, allowing it to adapt and improve its strategies over time by refining tactics based on these learning histories and retaining important knowledge for long-term use in North Korea’s cyber strategies. Noted security expert Bruce Schneier's recent proof-of-concept research unveils an innovative threat model that could be leveraged by North Korea given their history in producing wide scale attacks like WannaCry 2.0. This model highlights vulnerabilities in AI systems, including LLMs. This emerging form of automated attack is indicative of the evolution in cyber threats, where unsuspecting users unknowingly trigger deceptive commands embedded in multimedia content such as images or sound clips. When queried about these manipulated inputs, an AI chatbot either unveils the hidden prompt or follows the concealed instructions, sparking a range of harmful consequences. This is critical. It essentially means that attackers can manipulate systems like ChatGPT into performing actions that it normally should not, like executing harmful commands. Moreover, these strings can transfer to many closed-source, publicly-available chatbots, significantly amplifying the risk across widely used commercial models. Lastly, another study reveals how OpenAI’s GPT-3 and AI as-a-service products can automate spear-phishing by creating highly targeted emails. By employing machine learning and personality analysis, the study was able to generate phishing emails that were tailored to specific individual traits and backgrounds, resulting in messages that sounded “weirdly human.” Given that grammar errors often betray North Korean hackers, AI's capability to correct such mistakes, along with its inclusion of precise regional details like local laws, amplifies the authenticity of phishing endeavors. Despite the small sample size and the homogenous nature of the study, the research succeeded in demonstrating the potential of AI to outperform human-composed messages in spear phishing. This approach's success in creating convincing, individualized phishing emails highlights the alarming potential for AI to be used for malicious purposes in North Korea’s state-sponsored cyberattacks, and underscores the need for further exploration and defense strategies. Beyond automation, the rise of generative AI platforms such as Generated.Photos and ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com poses a complex threat. These platforms that craft convincing fake personas are more than a novel tech curiosity. They are a potential cybersecurity nightmare. For as little as $2.99, these lifelike avatars can be tweaked and animated, lending authenticity to fictitious profiles. While useful for legitimate purposes like video game development, North Korean hackers could exploit these tools to fabricate deepfakes for fraudulent schemes. A study even revealed that fake faces created by AI are considered more trustworthy than images of real people. Imagine a world where phishing scams and social engineering attacks are not perpetrated by crude caricatures, but instead by AI-generated personas that are indistinguishable from real people. This is a formidable gateway that North Korea could exploit, turning ingenuity into a clandestine weapon for cyber subterfuge. The potential implications extend beyond visual representations. AI-generated software is also capable of impersonating voices, a technique that has already been utilized in isolated fraudulent activities. For example, scammers were reported to have impersonated a chief executive’s voice to facilitate a fraudulent transfer of $243,000 from a U.K.-based energy firm, as detailed in the Wall Street Journal. While these developments and their implications underscore the growing complexity of cybersecurity in the age of AI, it is vital to approach the subject from a balanced perspective. The potential risks, though significant, must be weighed against the current state of technology, its accessibility, and the existing safeguards. The interplay of these factors should guide ongoing research, policy considerations, and risk management strategies to ensure that technologies are not exploited for malicious ends. Next Steps The immediate focus should be on discerning insights from previous cyberattacks to prepare for the potential of AI-integrated cyber warfare. As indicated earlier, North Korea's motivations for pursuing cyberattacks, particularly for financial gain, appear to be growing in the context of their economic challenges and an expanding nuclear program. Background discussions with experts in the field, including Jenny Jun, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, sheds further light on the unique characteristics and concerns associated with North Korea's approach to cyber warfare. Jun stated, What makes me most worried about North Korea’s cyber threat is that they are sometimes not afraid to launch operations that are brazen and destructive with a singular determination to achieve the task at hand, even if it means that their operations are less discreet as a result. For example, in 2018 North Korea reportedly destroyed 9,000 workstations and 500 servers through a wiper attack on Banco de Chile, in order to obfuscate investigation of a $10 million fraudulent SWIFT 1 transaction in a bank heist. Not only do such techniques increase the extent of the victim’s damage, they are indicative of a certain North Korean mindset that has a disregard for diplomatic consequences as a result of attribution. Her insights allow us to understand the urgency of understanding North Korea's approach and their behavior in the context of these advancements in AI. It is crucial to develop robust countermeasures to safeguard against an evolving and potentially more dangerous threat landscape. The right to privacy stands as a critical human rights concern for the foreseeable future. North Korea's conduct in cyber warfare clearly violates protection against interference with privacy in Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which North Korea has ratified. Further, the enigmatic nature of cyberattacks renders attribution highly elusive. Dr. Ethan Hee-Seok Shin, a legal analyst at Seoul-based NGO Transitional Justice Working Group, elucidated this paradox, noting the complex challenges of identifying culprits and attributing responsibility in cyber warfare. He stated, A hacker squad distributing malware has deniability that a military unit lobbing artillery shells over the border does not. The work of AI-curated identities presents a further legal conundrum since, to quote the Nuremberg judgment, crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced. Who should be put on trial? Clearly not the abstract AI-curated identities, but then their human creators or operators could plead that they never ordered an attack on a particular target. Shin's insights cast a stark light on the legal quagmire that defines cyber warfare. International law's enforcement becomes a Herculean task, especially against a nation like North Korea, which has repeatedly flouted agreements it has ratified and dismissed international norms. It is vital to recognize that the majority of North Korean hackers operate beyond their own borders, particularly in nations like China. This presents a perhaps underutilized strategic angle: the potential to exert diplomatic pressure on countries where these nefarious activities are being orchestrated, and imposing targeted sanctions against responsible individuals and entities in these countries. Shin, who recently testified at a congressional hearing, shed light on this issue. The hearing addressed China's complicity in North Korea's misdeeds, a subject that could create substantial discomfort in Beijing, as the Chinese government is keenly aware of its international reputation. Shin noted, "Beijing's entanglement in these activities places them in a precarious position; they do not wish to suffer reputationally due to their association with North Korea's wrongdoings." He further emphasized the necessity of collaborating with like-minded governments committed to halting these cyberattacks. While acknowledging the complexity of this endeavor, he asserts, “it is important to work with other cooperative governments who have interest to stop the cyberattacks from happening. It is not going to be easy, but it is something we can try.” As we traverse this complex landscape, it is evident that forming a united front is not just a choice, but a necessity. The ever-evolving tapestry of North Korea's cyber strategies stands as a testament to the urgency of innovative responses. By bringing into focus an internationally coordinated effort and a strategic emphasis on those who are complicit, like-minded nations can seek a path towards dismantling the legal and geopolitical challenges that arise. This approach underscores the importance of collective resilience and adaptability, which are critical for shaping the contours of a safer, more secure cyberspace. Tiana Lakhani is a rising junior at Stanford University, majoring in International Relations and planning for a prospective MA in East Asian Studies in her senior year. By Elizabeth Jean H. Kim, HRNK Research Intern

Edited by Raymond Ha, HRNK Director of Operations and Research The demographics of North Korean escapees reveals a notable gender gap between men and women.[1] Previous studies have already addressed how gender roles have influenced individuals’ decision to escape North Korea since the great famine in the late 1990s. However, the question of “What causes North Korean women to escape in much larger numbers than men?” requires further explanation. This article examines the gendered defection of North Koreans. Given my first-hand experiences as a North Korean refugee and hope to be a scholar of North Korean human rights issues, I am focusing on this research on how the gendered defection of North Koreans is related to structural factors and economic developments, including the rise of market activity during and after the famine of the 1990s. I also emphasize the pull factor of the gender imbalance in China, which led to the large-scale trafficking of North Korean women. Lastly, I argue that escapes from North Korea in recent years have been primarily influenced by family ties and social networks, sometimes involving escapees who have already resettled in South Korea. Structural Factors North Korea’s socialist system structurally segregates gender. Men are required to serve in the military for ten years, starting at the age of 17. During high school, all of my male classmates registered and took regular physical examinations under the local military mobilization department. After graduating, the majority entered military service. Only a few of my male classmates were waived from the military requirements, including those with physical disabilities, those who enrolled in college after being identified for their academic talent, and those with “unfavorable” family backgrounds due to guilt-by-association. On the other hand, only three of my female classmates—those over 5.2 feet (158 cm) tall—were qualified to serve in the military for eight years. Although I was also qualified for military service, I enrolled in college instead. Due to chronic malnutrition and forced labor from a very young age, the average height of North Korean women is smaller than South Korean women. According to a 2016 study, the difference is 3.3cm (162.3 cm vs. 159cm).[2] While North Korean men are tightly controlled under the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) in the public sphere, North Korean women mostly remain in the domestic sphere. If girls do not qualify for military recruitment or college enrollment, they automatically became members of the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League in workplaces and institutions, including textile factories and farms. Once these women get married, they are transferred from the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League to the Women’s Union, an official organization that is used for mobilizing North Korean women. Women remain members of the Women’s Union for life. Past Defections and the Impact of Marketization After the collapse of the socialist system and Kim Il-sung’s death in 1994, the public distribution system no longer provided enough goods or necessities for North Koreans.[3] The Kim Jong-il regime proclaimed the “Military First” ideology to reinforce national security. The regime continually recruited North Korean men into the military. Meanwhile, the KWP and the Kim Il-sung Socialist Youth League strictly controlled men who were disqualified from military service by making them work at industrialized facilities with almost no pay. At the time, my father’s official monthly salary was very low. We could barely buy 2 lb of pork, despite his relatively high position in a government-assigned job. My mom did not even calculate his salary in our family finances. Instead, we considered it as “free money.” One escapee I talked to told me that he had been a dam repairman in Ryanggang Province. He received 1,400 North Korean won per month for his work. “There was nothing I could do with this money, maybe I could buy 0.2 kilograms of rice,” he recalled. This reveals a glimpse of just how low official salaries were at the time. They were not enough for male North Korean workers to provide for their family’s basic needs. Instead, women sustained their families through economic activity at local markets, smuggling, developing private farms, and cultivating herbs. This economic activity had a direct influence on migration patterns. Female escapees who lived near the Chinese border (North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces) were more likely to escape due to the emergence of new economic activity. North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces are the focal points of illegal trade with China. According to South Korea’s Ministry of Unification, almost 80% of the 24,389 female North Korean escapees who have resettled in South Korea are from these two provinces.[4] During my nearly two-year confinement in a refugee camp during my journey to the United States, I met many female escapees from North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces. I was familiar with their northern accent, and I quickly noticed details about their background. Some were from the same town near the border with China, and some even went to the same school before leaving North Korea. Most of them left their hometown to seek economic opportunities or to pursue their personal aspirations for a better life, but they became victims of human trafficking in China. I also met female North Korean escapees from Pyongan Province. One of these women, P, had been born and raised in Pyongyang. After the public distribution system collapsed, however, she went to her aunt’s house in Musan County in North Hamgyong Province to make a living through smuggling. However, a woman in her aunt’s neighborhood approached her to suggest going to China to make money, luring her into sex trafficking and forced marriage with a Chinese man. During and immediately after the famine of the 1990s, fraud and lack of awareness also contributed to gendered defection. Living in a confined, overcrowded room in dire conditions with insufficient food at the refugee camp, I built rapport with many female North Korean refugees. I observed that the majority of North Korean women, especially those who escaped in the late 1990s and early 2000s, were tricked by their neighbors, friends, and sometimes even relatives into going to China, where they became victims of human trafficking. This has also been documented by researchers. For example, one North Korean escapee went to China with her friend and her friend’s father to try and find her two sisters, who had already escaped to China and had been forced to marry Chinese men. However, after crossing the Tumen River, her friend’s father sold her to a Chinese man instead.[5] After the famine, China became North Korea’s most significant trade partner. Chinese companies collected natural resources from North Korea, like wood, medicinal herbs, and mineral resources. Those who live near the border with China rely on exchanging natural resources and other trade to make a living. One such North Korean escapee, C, went to collect blueberries near Baekdu Mountain with her friends, but ended up reaching a Chinese village by accident. “I did not know how to go back home,” she told me. Lacking information or reliable social networks, North Korean women who arrive in China often become victims of trafficking. According to one estimate, approximately 70% to 80% of North Korean women who cross into China fall victim to human trafficking.[6] Pull Factors Gendered North Korean defection is directly reflected in pull factors on the Chinese side. The gender imbalance resulting from decades of enforcing the “one-child policy,” combined with traditional gender norms, created a “demand” for North Korean women, who are sold into marriage and kept in captivity. In contrast, the pull factor of North Korean men to China is relatively low. North Korean men find work on hidden farms or in the lumber industry in northern China through an underground labor market. They are severely exploited by their Korean-Chinese employers. Mr. C, who joined our group of escapees in Shenyang after being released from a long-term prison labor facility in North Korea, said that he crossed the border into China to earn money to support his family. Once he arrived in China, he connected with his friend, who was already working in a lumber facility in Changchun. The living and working conditions there were horrific. Even worse, his employer was unwilling to pay the North Korean workers and reported them to the police. The workers were subsequently repatriated to North Korea. Another male escapee pointed out to me that “we knew that we would not be welcome in China even if we escaped there, and there is nothing we can really do.” Contemporary Trends In recent years, escapes from North Korea are more likely to be related to social networks and human capital. Even after Kim Jong-un further tightened border security upon coming to power, there was still a gender imbalance among escapees who arrived in South Korea. The number of North Korean women who escaped to South Korea after living in China is relatively higher than those who directly crossed the border from North Korea. NGOs and South Korean missionaries play an important role here. I was rescued by a South Korean missionary organization while I was in China. With their help and protection, I successfully reached out to a third country where I could claim my status as a refugee. In my group, six out of eight had been rescued by the same organization from China, and only two had recently left North Korea with help from family members who had already resettled in South Korea. I learned in the refugee camp that there were large numbers of female North Korean escapees who had been rescued by NGOs and mission organizations, many of them from China. Nevertheless, the gender gap among escapees has shrunk since 2021 due to the regime’s COVID-19 restrictions. The small number of escapees who arrived during the pandemic could do so thanks to the help of family members and other social networks, making it easier to navigate their journey to South Korea. It is likely that these recent escapees had been trapped in China for a while, and could sustain themselves with the support of family members who were already living in South Korea. By contrast, it is now difficult for North Korean women in China to escape unless they have family members or relatives who can help. Due to advanced surveillance technology and restrictions on movement, there are greater risks in rescuing North Korean women from China. Moreover, the cost is much higher than before. In the case of K, a female escapee who arrived in South Korea in 2020, both of her parents had already been living in South Korea for a decade. With her parents’ support, K was successfully rescued from North Korea and arrived in South Korea in the middle of the pandemic. Concluding Remarks The decision to escape from North Korea must be examined from multiple perspectives, including structural factors, economic changes, the power of women’s economic contribution, regional mobility, and the pull factor resulting from the gender imbalance in China. During and shortly after the famine of the 1990s, gendered defection directly reflected institutionalized gender separation within North Korea. Economic devastation pushed North Korean women, mostly from North Hamgyong and Ryanggang provinces, to go to China to seek economic opportunities or to achieve their personal aspirations. However, upon arriving in China, North Korean women were often lured into sex trafficking networks through fraud and deception. Moreover, the gendered defection of North Koreans must be understood with reference to the gender imbalance in China. It is in this context that many North Korean women were sold to poor rural Chinese men. In recent years, escapes from North Korea have been more closely related to family ties and social networks. The latter includes NGOs and religious organizations. Overall, the number of escapees has drastically dropped over the past couple of years. To rescue North Korean women in China who have fallen victim to trafficking, more NGOs and international humanitarian organizations must pay attention to these issues as serious violations of human rights. The international community must pressure China to take responsibility for and assist trafficked North Korean women. China can take tangible steps, such as providing them with a legal basis for staying in China and facilitating humanitarian protection. For North Koreans who newly escape to China, the Chinese government should create a new category of asylum seekers and allow a temporary immigration status instead forcibly repatriating them. Elizabeth Jean H. Kim (pseudonym) is a North Korean refugee student who studied Sociology and International Relations at the University of Southern California. [1] Ministry of Unification, “Number of North Korean Defectors Entering South Korea,” accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/whatwedo/support/. [2] Cho Eun-ah, “韓여성 키 162㎝… 100년새 20㎝ ‘폭풍 성장’ 세계 1위” [South Korean Women are 162cm on Average – 20cm Growth over the Past 100 Years], Dong-A Ilbo, July 27, 2016. https://www.donga.com/news/Society/article/all/20160727/79419892/1. [3] Fyodor Tertitskiy, “Let them eat rice: North Korea’s public distribution system,” NK News, October 29, 2015. https://www.nknews.org/2015/10/let-them-eat-rice-north-koreas-public-distribution-system/. [4] Ministry of Unification, “Policy on North Korean Defectors,” accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/relations/statistics/defectors/. [5] Lives for Sale: Personal Accounts of Women Fleeing North Korea to China (Washington, D.C.: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2009), 33. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Lives_for_Sale.pdf. [6] Ahn So-young, “국제법률단체 ‘탈북 여성들 중국 동북3성에서 성착취…국제사회 대응 시급’” [The Sexual Exploitation of North Korean Women in Northeastern China Requires Urgent International Attention, says NGO], VOA Korea, March 27, 2023. https://www.voakorea.com/a/7024247.html. By Daniel McDowall, former HRNK Research Intern