|

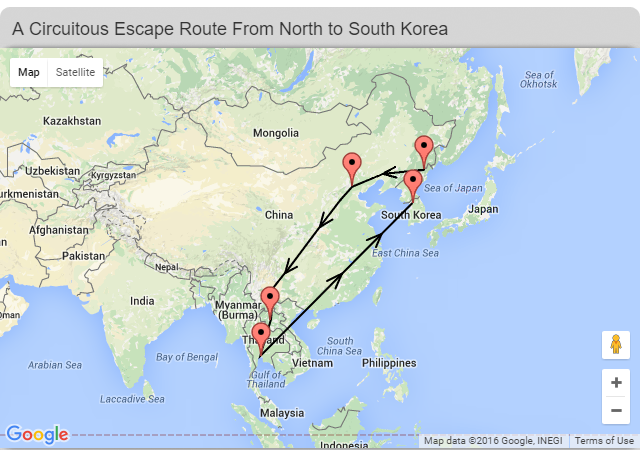

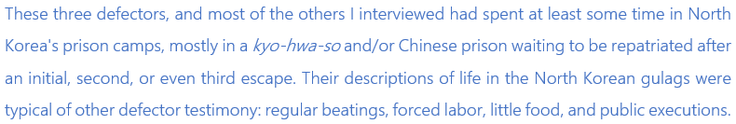

By Chris Buchman, HRNK Research Intern April 2016 I spent some time as a field officer with a North Korean humanitarian NGO interviewing North Korean defectors who had just completed their long and harrowing journeys from the sub-arctic climate of northeastern China to humid and sweaty Southeast Asia. I was tasked with conducting monitoring and evaluations interviews; that is, asking defectors about their lives in North Korea, under what circumstances they went to China, how they spent their time in China, and whether or not they had any issues during their escapes to Southeast Asia. Quite often, though, the defectors were so relieved to have completed the home-run stretch to a new and better life that our interviews quickly transformed into heart-to-heart discussions about their hopes, dreams, and worries for the future. Image credit: PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wideangle/episodes/crossing-heavens-border/map-a-circuitous-escape-route-from-north-to-south-korea/?p=5020. One interviewee, a man in his early forties, said excitedly that the first thing he wanted to do upon settling into life in South Korea was get a driver's license and become a taxi driver. He said that in North Korea, being a driver was a well-respected and potentially lucrative profession because you had access to a means of motorized transportation, something that not many people in North Korea had and thus was in very high demand. A former beekeeper in her early twenties told me that her dream was to become a teacher in South Korea. She was worried, though, that because she had never even been able to complete elementary school, she was too old and it would be too late for her to complete her education and follow her dreams. A middle-aged woman intending on resettling in the USA wondered what she might be able to do for work there. We brainstormed a bit, and she said she had been a farmer in North Korea, so perhaps she could do that upon resettlement as well. I had to explain to her that farming in the U.S. was done mostly by machines on huge tracts of land requiring little human labor. At hearing this, she seemed more than a bit dejected about her prospects for the future. However, listening to these defectors' stories it became apparent that the real human rights violation that the North Korean government perpetrates on its people is not so much these physical and mental hardships they're made to endure, but rather it is the complete denial of personal agency. Many of the defectors I spoke with had spent so much time and effort evading authorities, navigating a corrupt bureaucracy, and forging a livelihood in an incredibly insecure economy, where almost everything they did to get by was illegal, that going to prison at some point was simply a matter of course. Years of their lives were spent struggling to do things that people living in nations with good governance don't think twice about, and then months or years of their lives were stolen from them when they were sent to prison for trying to exercise rights guaranteed unto them by globally recognized human rights conventions. For many of these defectors, watching a public execution or being beaten by an authority figure were things that were so routinized that the defectors didn't even seem phased by discussing them. Compared to their South Korean brethren, North Korean defectors tend to arrive in South Korea (or one of several other countries that accept North Korean refugees) lacking in education and job skills, susceptible to being taken advantage of economically, intellectually, and sexually, and looking noticeably older and less healthy. It's a long, hard, uphill journey for North Korean defectors to reach a state of social equity with South Koreans, a journey that few complete. This is evident in the fact that the North Korean defector population has a suicide rate two to six times higher than that of the general South Korean population, which is already the highest among OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations. [1] Some of my North Korean interviewees have become good friends and still keep in touch. Some of them have quite successfully adjusted to life in their new homes; they use smartphones, drive cars, are thriving socially, and are doing well enough financially to regularly send remittances to their families back in North Korea, enabling those family members to live better lives and potentially even escape North Korea themselves. Enabling North Korean defectors in this way is one of the best weapons we have in fighting the North Korean regime's cycle of repression, and one of the best hopes for effecting change in a country where the freedom to pursue one's dreams is oftentimes illegal. [1] Stephen Evans, Korea's Hidden Problem: Suicidal Defectors, BBC News, Nov. 5, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34710403.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

DedicationHRNK staff members and interns wish to dedicate this program to our colleagues Katty Chi and Miran Song. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed